Chitin is a naturally occurring polymer with a number of attractive mechanical and chemical properties that many are seeking to mimic in bioengineered materials. Naturally occurring chitin has one of two crystal structures known as α – with the molecules aligned antiparallel – and β – with the molecules aligned in parallel. The nanoscale structure of chitin greatly affects the chemical and mechanical properties of the material, and here the structure that water forms around the fibres when they are hydrated can play a significant role. However, until now the details of these different structures were not well understood. Now researchers led by Ayhan Yurtsever and Takeshi Fukuma at Nano Life Science Institute (WPI-NanoLSI), Kanazawa University, together with collaborators Kazuho Daicho, Tsuguyuki Saito, and Noriyuki Isobe from the University of Tokyo, and molecular dynamics experts led by Fabio Priante and Adam S. Foster from Aalto University, Finland, have used 3D AFM and molecular dynamics to study the different structures and how water forms on them when they are hydrated for different pH levels (Fig. 1) The results of this study provide explanations for differences in how the two structures interact with enzymes and reactants.

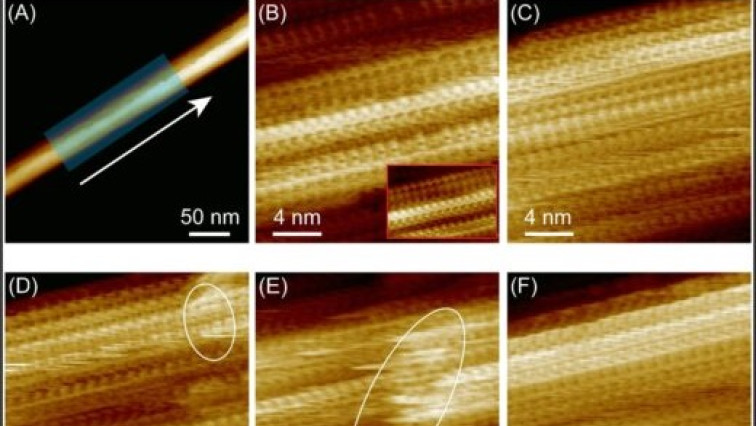

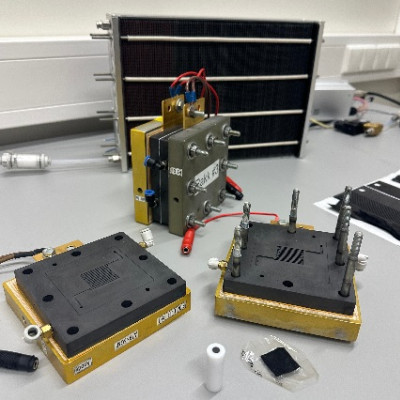

Atomic force microscopy gauges surface topography and chemical information by monitoring the strength of forces exerted on a nanoscale tip attached to a cantilever. The researchers used a modified AFM known as 3D-AFM, which enabled them not only to image the morphology of chitin nanocrystals but also to investigate the three-dimensional local organization of water molecules surrounding these nano structures. In their report, they noted a high degree of long-range order in the β chitin fibres, whose structure has so far been less thoroughly explored. They describe how the occasional breaks in that order “lead to a structure resembling partially bitten corncobs or a brickwork pattern”. Their AFM imaging also showed how the molecular arrangement runs right through the fibre. “These different structural components are not merely external aggregates;” they explain in the report. “Instead, they constitute an integral part of the chitin fiber(Fig. 2).”

The researchers also investigated the structures under different pHs, to see how this might affect the hydrated architectures of the chitin fibres. They found that the high level of crystallinity observed was preserved in acetic acid buffer solutions pH 3-5. Some of the most significant insights came from studying the water structure and hydrogen bonding on the two crystalline types of chitin (Fig. 3) They showed how the larger grooves in α chitin allowed greater accumulation of water, which formed a hydration barrier for interactions with external ions and molecules making them less reactive. The repulsive forces for hydration were also higher for α chitin. They suggest this may explain why certain enzymes react with chitin in only one crystalline form and not the other. Furthermore, they propose that the lower energetic penalty associated with the structured hydration environment of β-chitin facilitates more rapid enzymatic access and substrate turnover. These insights could inform the development of bioprotonic applications– devices based on the transport of protons as opposed to electronics – and hydrogels since the hydration layer affects ion and molecular diffusion.

“Collectively, this work links nanoscale interfacial structure to rational design strategies, advancing the effective development of sustainable, bio-based nanomaterials for energy and biomedical applications,” they conclude in their report. “Additionally, it provides valuable insights for the computational modeling of chitin surface interactions, crystallosolvate formation, and enzymatic hydrolysis, supporting the development of future material design strategies.”

Read the original article on Kanazawa University.