In a field near Poochera on South Australia's Eyre Peninsula is a deposit of white clay. It's a mineral called kaolin — a type of clay historically used in the production of glossy white paper, as well as in clay-based ceramics, cement and fibreglass.

But this deposit is special. It is what is known as halloysite, a type of kaolin where, at a molecular level, it forms into a unique structure: nanotubes.

A nanotube is a cylinder-shaped molecule made from a single layer of atoms. Normally researchers have to produce them with expensive processes.

Tony Belperio, the director of Minotaur Exploration — the company behind the project — said this deposit was overflowing with natural nanotubes.

"This deposit is the largest we know of in the world," he said.

"There are some small deposits in New Zealand and in the US, and there was one in China but it's pretty much run out. When we took the material to the nanotechnology team at the University of Newcastle, they were very surprised when they saw these things."

"They're used to doing experiments with carbon nanotubes, which are very expensive to produce. When they found out we had millions of tonnes of this material, they were a little bit gobsmacked."

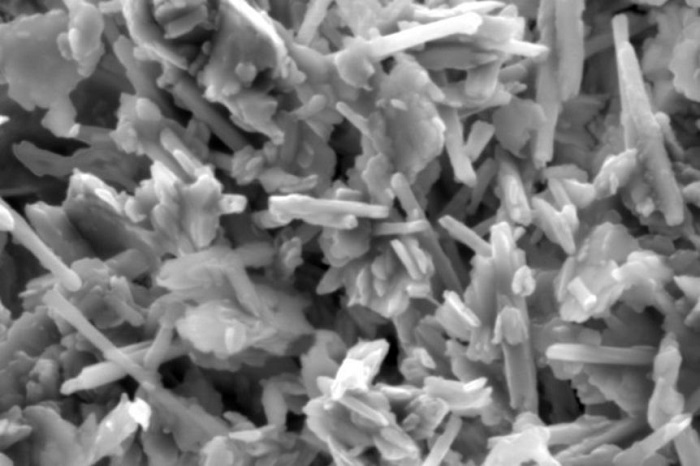

An electron microscope image showing the close-up structure of halloysite, with the nanotubes and regular kaolin platelets visible.

A powerful tool of the future

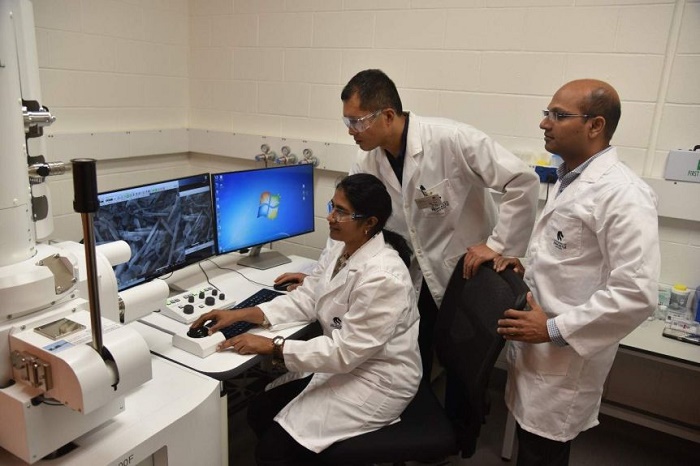

Professor Ajayan Vinu is the head of the Global Innovative Centre for Advanced Nanomaterials (GICAN) at the University of Newcastle and has been working with the halloysite.

Dr Vinu said, while the material itself could be used to create nanotechnology, its true strength was that it could be used as a template to create other advanced nanomaterials.

"It's like making a brick. To make a brick you need a mould, you just reduce the size to 100,000 times smaller," Dr Vinu said.

"So, we use the nanotube as a mould to make nanocarbons with a very high surface area and a high volume. The material we've made is of low cost, with a high performance, and we can modify it to specifically absorb CO2 from a mixture of gases, up to 1.1 tonne of CO2 per tonne of the material."

This was not just a theory, according to Dr Vinu. He said they had been able to successfully create the carbon-capturing molecules, which came in the form a black pellet.

"We've established a pilot plant at GICAN so we're able to make tonnes of the material in house," he said.

"The next challenge is to make the carbon capture pilot plant, so that's what we're doing in this next six to eight months."

But it was once the CO2 was captured that things got interesting. "We are trying to convert the captured CO2 into methanol, using sunlight and water," Dr Vinu said.

"The methanol that is produced can be used as a fuel in a fuel cell that produces cleaner energy."

The halloysite nanotubes have dramatically accelerated research at the University of Newcastle.

The next step

Dr Vinu and the team at GICAN are already working on a significantly improved version of the nanocarbon.

"We have developed another nanocarbon material that could absorb almost two tonnes of CO2 per tonne of the material," he said.

"If we can get the material right and install it in the power plants of CO2-producing industries, we can significantly reduce CO2 emissions."

"The global market for this kind of technology is worth almost $30 billion. We could create a new industry and lots of jobs for Australians while also fighting climate change."

Read the original article on ABC News.