2022-11-21

Visited : 1361

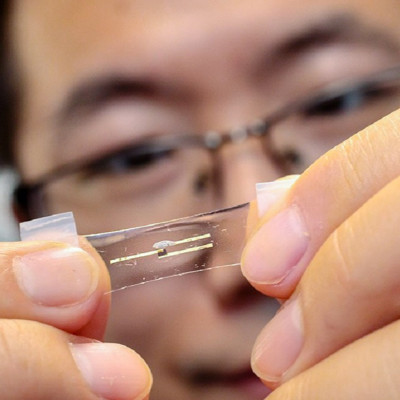

Neuromorphic chip consists of a thin film plastic semiconductor combined with stretchable gold nanowire electrodes.

Flexible, wearable electronics are making their way into everyday use, and their full potential is still to be realised. Soon, this technology could be used for precision medical sensors attached to the skin, designed to perform health-monitoring and diagnosis.

Such a skin-like device is being developed in a project between the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME).

Worn routinely, future wearable electronics could potentially detect possible emerging health problems even before obvious symptoms appear. A device could also perform a personalised analysis of the tracked health data while minimising the need for its wireless transmission.

It would, however, need to collect and process a vast amount of data, well above what even the best smartwatches can do today, and with very low power consumption in a very tiny space.

To address this need, the team employed neuromorphic computing – an artificial intelligence (AI) technology which mimics the operation of the brain by training on past data sets and learning from experience. Its advantages include compatibility with stretchable material, lower energy consumption and faster speed than other types of AI.

The other major challenge the team faced was integrating the electronics into a skin-like stretchable material. The key material in any electronic device is a semiconductor and in current rigid electronics used in cell phones and computers, this is normally a solid silicon chip. Stretchable electronics require the semiconductor to be a highly flexible material that is still able to conduct electricity.

The team’s skin-like neuromorphic chip consists of a thin film plastic semiconductor combined with stretchable gold nanowire electrodes. Even when stretched to twice its normal size, the device functions as planned, without forming any cracks.

In one test, the team built an AI device and trained it to distinguish healthy electrocardiogram (ECG) signals from four different signals indicating health problems. After training, the device was more than 95% effective at correctly identifying the ECG signals.

Exposure to an intense X-ray beam revealed how the molecules that make up the skin-like device material re-organise upon doubling in length. These results provided molecular-level information to better understand the material properties.

Read the original article on Innovation in Textiles.