When SARS-CoV-2 was identified as the virus that causes COVID-19 in January, Novavax was one of the first companies to disclose that it was working on a vaccine for it. Now a Phase I clinical trial testing the safety of that experimental vaccine is scheduled to begin this month in Australia. That trial will make it one of the first 10 vaccines to enter clinical testing since the pandemic began.

CEPI, a nonprofit organization that funds infectious disease vaccine development, counts at least 115 vaccine programs underway for SARS-CoV2. So far, it has provided funding to nine of them, including front-runner vaccines made by Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Moderna, and the University of Oxford.

Before today, CEPI had invested $58 million across all of its COVID-19 vaccine efforts, including an initial $4 million for Novavax. The new $384 million commitment to Novavax is the largest investment CEPI has ever made in a single vaccine. The move pushes the biotech firm into the limelight and will help diversify the kinds of technologies at the forefront of the COVID-19 vaccine race. Among the 10 front-runners, Novavax is the only one developing a nanoparticle-based vaccine.

The Gaithersburg, Maryland–based company has a history of developing vaccines for emerging infectious diseases. It previously made experimental vaccines for Ebola, Zika, and two other coronaviruses: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). None of these vaccines reached the advanced stages of testing to prove whether they were effective or not.

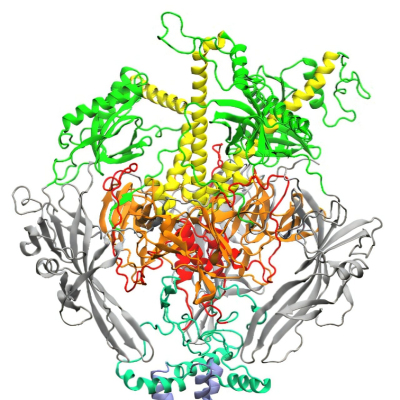

Novavax’ vaccine is based on recombinant spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2. The coronavirus uses its spike proteins to recognize and enter human cells. Nearly all COVID-19 vaccines share a similar goal of trying to get the immune system to recognize and stop the spike proteins from latching onto human cells. To make its nanoparticle vaccine, Novavax combines these spike proteins with a mixture of cholesterol, phospholipids, and saponins—plant-derived compounds used to help activate the immune system.

The nanoparticle approach is different from those in many of the most advanced and well-funded COVID-19 vaccine programs, which use genetic vaccines to deliver a set of RNA or DNA instructions into our cells for making the spike protein. For instance, Inovio is making a DNA vaccine, and Moderna, Pfizer, and Sanofi all have mRNA vaccine programs. Others groups such as CanSino Biologics, Johnson & Johnson, and the University of Oxford are using genetically engineered common cold viruses to deliver DNA for the spike protein into our cells.

Importantly, none of these methods is used to make commercial vaccines for humans—although COVID-19 could change that. Novavax expects to have results from its Phase I safety study in July. It plans to begin a larger Phase II study of its vaccine in multiple countries soon after. The firm says it could produce up to 100 million doses of the vaccine by the end of 2020 and potentially more than 1 billion doses in 2021.

In March, Novavax signed a deal with its Gaithersburg neighbor, Emergent BioSolutions, to manufacture its experimental COVID-19 vaccines and its experimental flu vaccine, NanoFlu. Emergent will make the spike proteins for the COVID-19 vaccine in vats of genetically engineered insect cells. The approach is an alternative to the traditional method of making vaccines in chicken eggs.

Read the original article on C&EN.