The method involves spraying methylcellulose, a renewable plastic material derived from plant cellulose, on 3D-printed and other objects ranging from electronics to plants, according to a Rutgers-led study in the journal Materials Horizons.

“This could be the first step towards 3D manufacturing of organs with the same kinds of amazing properties as those seen in nature,” said senior author Jonathan P. Singer, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering in the School of Engineering at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. “In the nearer term, N95 masks are in demand as personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic, and our spray method could add another level of capture to make filters more effective. Electronics like LEDs and energy harvesters also could similarly benefit.”

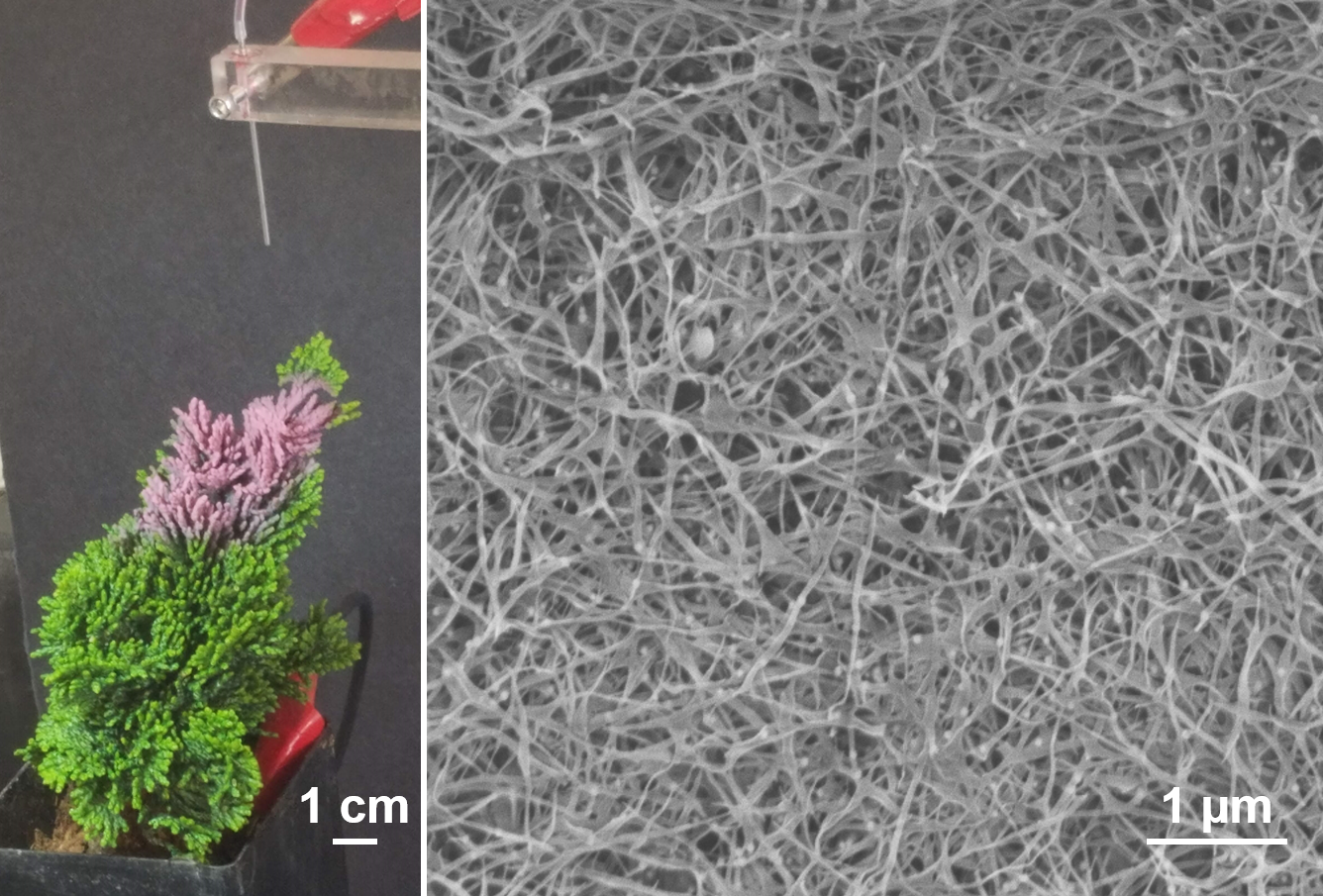

Photo (left) of a nanowire forest being sprayed on a miniature tree, with color (purple) arising from embedded gold nanoparticles. Electron microscope image (right) of the nanowire/nanoparticle blend. Images: (left) Jonathan P. Singer; (right) Lin Lei

Thin wires (nanowires) made of soft matter have many applications, including the cilia that keep our lungs clean and the setae (bristly structures) that allow geckos to grip walls. Such wires have also been used in small triboelectric energy harvesters, with future examples possibly including strips laminated on shoes to charge a cell phone and a door handle sensor that turns on an alarm.

While people have known how to create nanowires since the advent of cotton candy melt spinners, controlling the process has always been limited. The barrier has been the inability to spray instead of spin such wires.

Singer’s Hybrid Micro/Nanomanufacturing Laboratory, in collaboration with engineers at Binghamton University, revealed the fundamental physics to create such sprays. With methylcellulose, they have created “forests” and foams of nanowires that can be coated on 3D objects.

They also demonstrated that gold nanoparticles could be embedded in wires for optical sensing and coloration.

Read the original article on Rutgers University.