The research team led by Professor Sang Ouk Kim at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering published their work in Nature Communications.

Hydrogen is likely to play a key role in the clean transition away from fossil fuels and other processes that produce greenhouse gas emissions. There is a raft of transportation sectors such as long-haul shipping and aviation that are difficult to electrify and so will require cleanly produced hydrogen as a fuel or as a feedstock for other carbon-neutral synthetic fuels. Likewise, fertilizer production and the steel sector are unlikely to be “de-carbonized” without cheap and clean hydrogen.

The problem is that the cheapest methods by far of producing hydrogen gas is currently from natural gas, a process that itself produces the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide–which defeats the purpose.

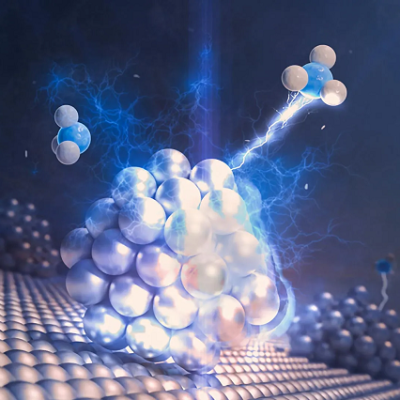

Alternative techniques of hydrogen production, such as electrolysis using an electric current between two electrodes plunged into water to overcome the chemical bonds holding water together, thereby splitting it into its constituent elements, oxygen and hydrogen are very well established. But one of the factors contributing to the high cost, beyond being extremely energy-intensive, is the need for the very expensive precious and relatively rare metal platinum. The platinum is used as a catalyst–a substance that kicks off or speeds up a chemical reaction–in the hydrogen production process.

As a result, researchers have long been on the hunt for a substitution for platinum -- another catalyst that is abundant in the earth and thus much cheaper.

Transition metal dichalcogenides, or TMDs, in a nanomaterial form, have for some time been considered a good candidate as a catalyst replacement for platinum. These are substances composed of one atom of a transition metal (the elements in the middle part of the periodic table) and two atoms of a chalcogen element (the elements in the third-to-last column in the periodic table, specifically sulfur, selenium and tellurium).

What makes TMDs a good bet as a platinum replacement is not just that they are much more abundant, but also their electrons are structured in a way that gives the electrodes a boost.

In addition, a TMD that is a nanomaterial is essentially a two-dimensional super-thin sheet only a few atoms thick, just like graphene. The ultrathin nature of a 2-D TMD nanosheet allows for a great many more TMD molecules to be exposed during the catalysis process than would be the case in a block of the stuff, thus kicking off and speeding up the hydrogen-making chemical reaction that much more.

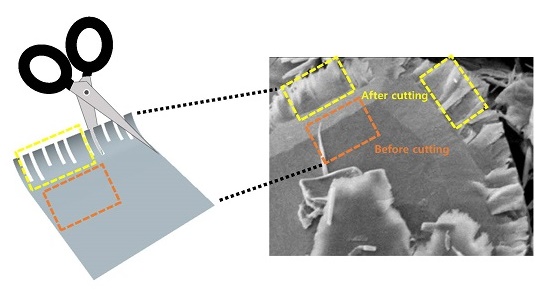

Schematic view of scissoring 2D sheets to nanoribbon.

However, even here the TMD molecules are only reactive at the four edges of a nanosheet. In the flat interior, not much is going on. In order to increase the chemical reaction rate in the production of hydrogen, the nanosheet would need to be cut into very thin – almost one-dimensional strips, thereby creating many edges.

In response, the research team developed what are in essence a pair of chemical scissors that can snip TMD into tiny strips.

“Up to now, the only substances that anyone has been able to turn into these ‘nano-ribbons’ are graphene and phosphorene,” said Sang Professor Kim, one of the researchers involved in devising the process.

“But they’re both made up of just one element, so it’s pretty straightforward. Figuring out how to do it for TMD, which is made of two elements was going to be much harder.”

The ‘scissors’ involve a two-step process involving first inserting lithium ions into the layered structure of the TMD sheets, and then using ultrasound to cause a spontaneous ‘unzipping’ in straight lines.

“It works sort of like how when you split a plank of plywood: it breaks easily in one direction along the grain,” Professor Kim continued. “It’s actually really simple.”

The researchers then tried it with various types of TMDs, including those made of molybdenum, selenium, sulfur, tellurium and tungsten. All worked just as well, with a catalytic efficiency as effective as platinum’s.

Because of the simplicity of the procedure, this method should be able to be used not just in the large-scale production of TMD nanoribbons, but also to make similar nanoribbons from other multi-elemental 2D materials for purposes beyond just hydrogen production.

Read the original article on Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).