The scientists have published their findings, obtained in collaboration with researchers from Bielefeld University's Medical School OWL and Justus Liebig University Giessen, in the Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology.

‘The study shows that the helium ion microscope is suitable for imaging coronaviruses – so precisely that the interaction between virus and host cell can be observed,’ says physicist Dr Natalie Frese. She is the lead author of the study and a researcher in the research group Physics of Supramolecular Systems and Surfaces at the Faculty of Physics.

Coronaviruses are tiny – only about 100 nanometres in diameter, or 100 billionths of a metre. So far, mainly scanning electron microscopy (SEM) has been used to examine cells infected with the virus. With SEM, an electron beam scans the cell and provides an image of the surface structure of the cell occupied by viruses.

However, SEM has a disadvantage: the sample becomes electrostatically charged during the microscopy process. Because the charges are not dispersed from non-conductive samples, for example viruses or other biological organisms, the samples must be coated with an electrically conductive coating, such as a thin layer of gold.

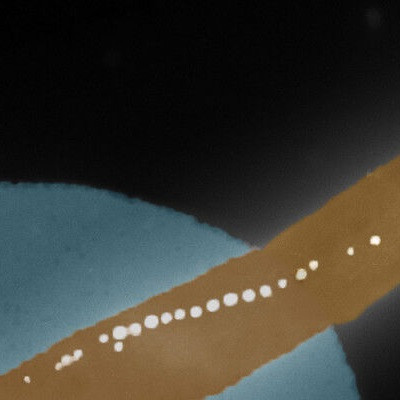

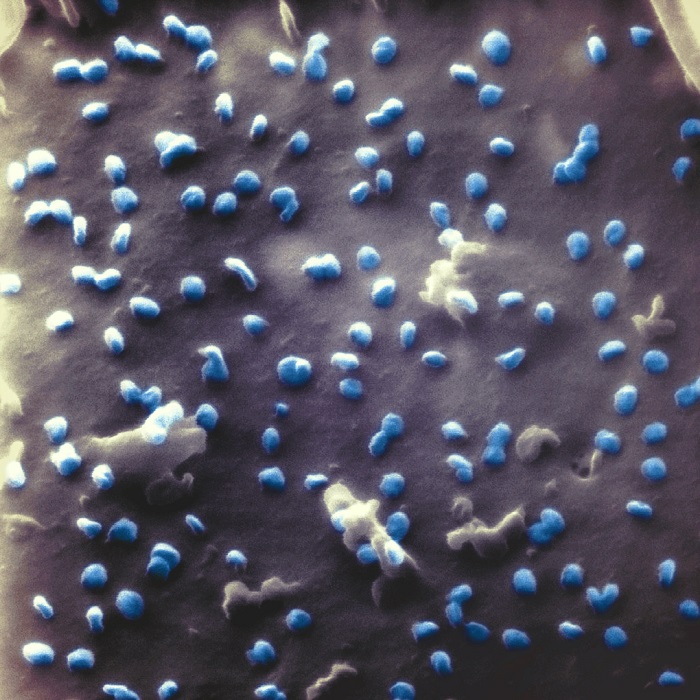

Coronaviruses (blue) exiting a kidney cell, images captured with a helium ion microscope.

‘However, this conductive coating also changes the surface structure of the sample. Helium ion microscopy does not require a coating and therefore allows direct scanning,’ says Professor Dr Armin Gölzhäuser, who heads the research group Physics of Supramolecular Systems and Surfaces.

With the helium ion microscope, a beam of helium ions scans the surface of the sample. Helium ions are helium atoms that are each missing an electron – they are therefore positively charged. The ion beam also charges the sample electrostatically, but this can be compensated for by additionally irradiating the sample with electrons.

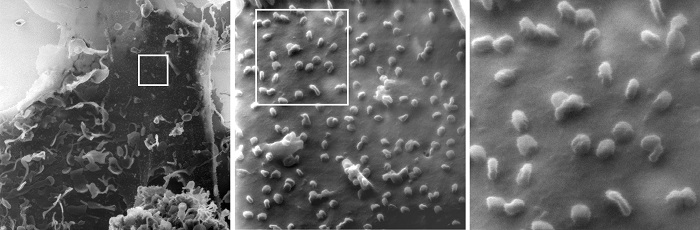

Furthermore, the helium ion microscope has a higher resolution and a greater depth of field.In their study, the scientists infected cells – artificially produced from the kidney tissue of a species of monkey – with SARS-CoV-2 and studied them in dead state under the microscope. ‘Our images provide a direct view of the 3D surface of the coronavirus and the kidney cell – with a resolution in the range of a few nanometres,’ says Frese. This enabled the researchers to visualise interactions between the viruses and the kidney cell.

Their study results indicate, for example, that helium ion microscopy can be used to observe whether individual coronaviruses are just lying on the cell or are bound to it. This is important in order to understand defence strategies against the virus: an infected cell can bind the viruses, which have already multiplied inside it, to its cell membrane on exit and thus prevent them from spreading further.

A kidney cell infected with SARS-CoV-2 under the helium ion microscope (sectional magnification from left to right, a single virus is about 100 nanometres in size): the images indicate that some coronaviruses only lie loosely on the cell as they exit, while other viruses are bound to the cell.

‘Helium ion microscopy is well suited for imaging the cell’s defence mechanisms that take place at the cell membrane,’ says virologist Professor Dr Friedemann Weber, too. He is investigating SARS-CoV-2 at Justus Liebig University in Gießen and collaborated with the Bielefeld researchers on this study.

Professor Dr Holger Sudhoff, head physician at the University Clinic for Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Medical School OWL at Bielefeld University, adds: ‘This method is a significant improvement for imaging the SARS-CoV-2 virus interacting with the infected cell. Helium ion microscopy can help to better understand the infection process in COVID-19 sufferers.’Helium ion microscopy is a comparatively new technology.

In 2010, Bielefeld University became the first German university to acquire a helium ion microscope, which is used primarily in nanotechnology. Worldwide, helium ion technology is still rarely used to examine biological samples. ‘Our study shows that there is great potential here,’ says Gölzhäuser. The study appears in a special issue of the Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology on the helium ion microscope.

Read the original article on Bielefeld University.