The team, led by Yasutomo Segawa, associate professor at the Institute for Molecular Science, part of the National Institutes of Natural Science (NINS) in Japan, set out to synthesize curved, infinitely stacking nanographenes -- like potato chips in a cardboard can -- that can assemble into nanowires. The results were published on March 24 in Journal of the American Chemical Society.

"Effectively stacked hydrocarbon wires have the potential to be used as a variety of nano-semiconductor materials," Segawa said. "Previously, it has been necessary to introduce substituents that are not related to or inhibit the desired electronic function in order to control the assembly of the wires."

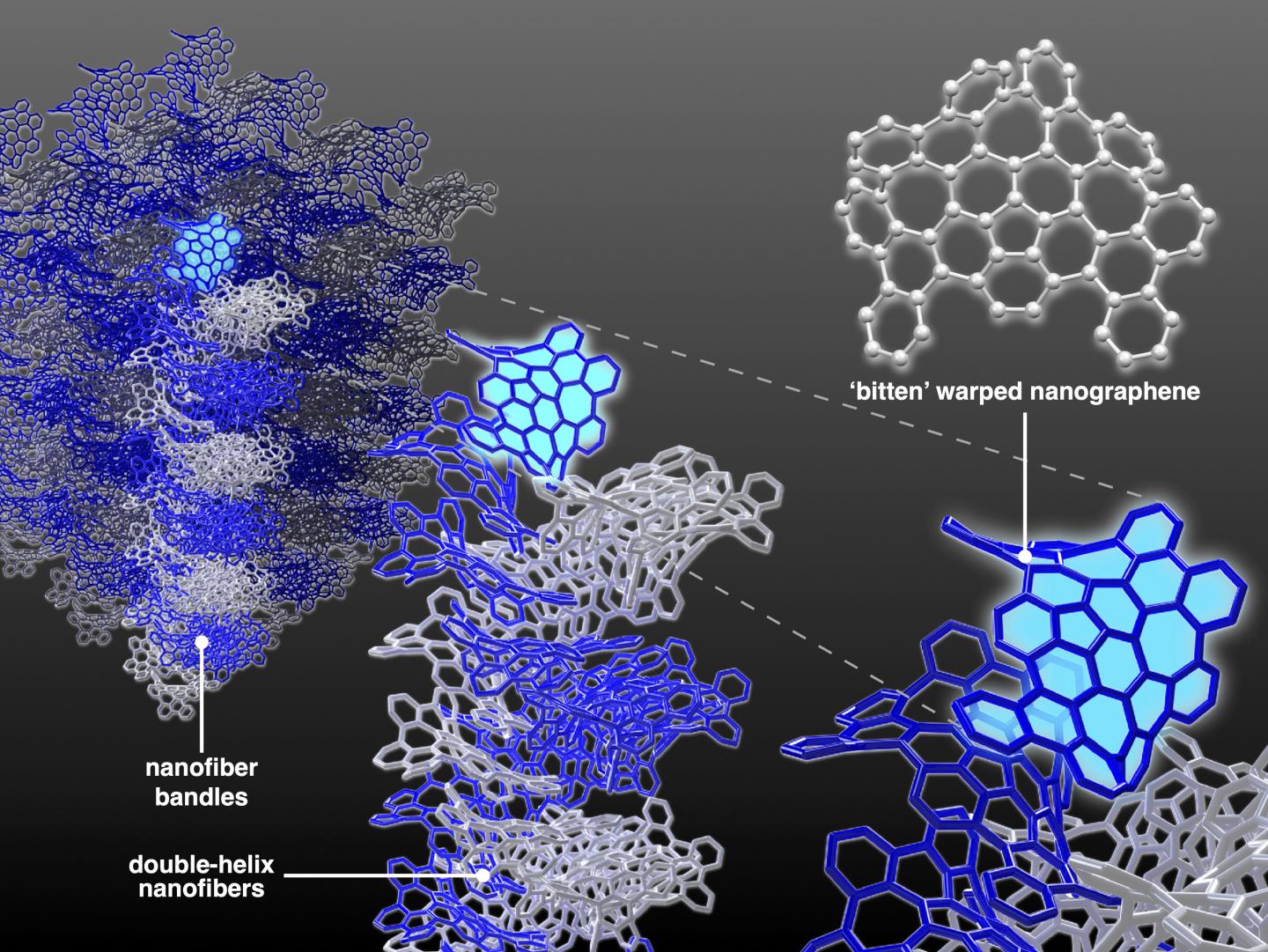

Schematic illustration of hierarchical structures of carbon nanofiber bundles made of bitten warped nanographene molecules.

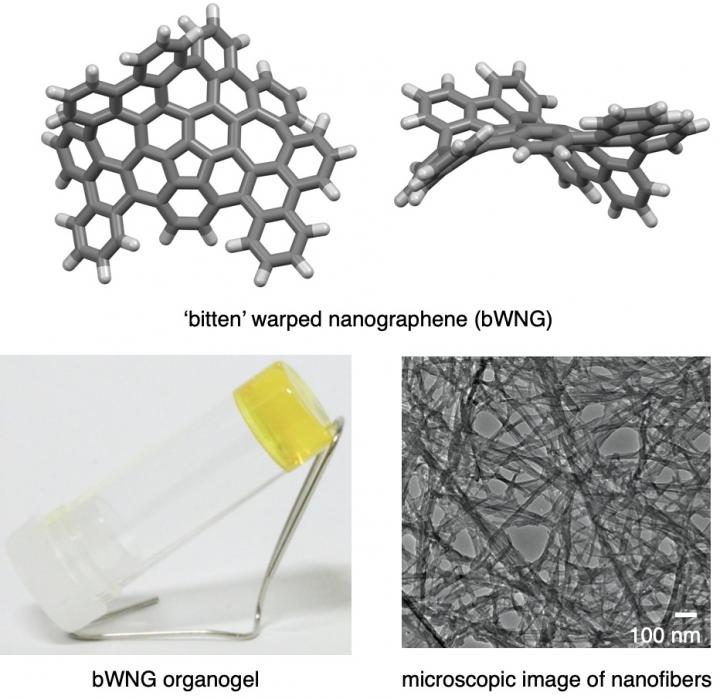

By removing substituents, or additives, from the fabrication process, researchers can develop molecular materials that have a specific, desired electronic function, according to Segawa. With this goal in mind, the team developed a molecule called 'bitten' warped nanographene (bWNG), with 68 carbon atoms and 28 hydrogen atoms forming a 'bitten apple' shape. Created as a solution, when left to evaporate over 24 hours in the presence of hexane -- an ingredient in gasoline with six carbon atoms -- bWNG becomes a gel.

Upper panel shows the molecular structure of 'bitten' warped nanographene (bWNG). Lower left shows a photograph of bWNG organogel and Lower right shows a microscopic image of nanofibers made of bWNG.

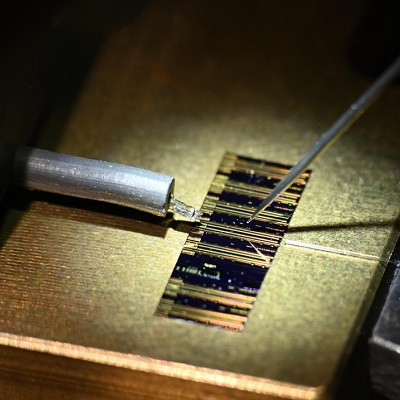

The researchers attempted to recrystallize the molecules of the original solution to examine the specific structure of the bWNG gel through X-ray crystallography. This technique can reveal the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal by irradiating the structure with X-rays and observing how they diffract.

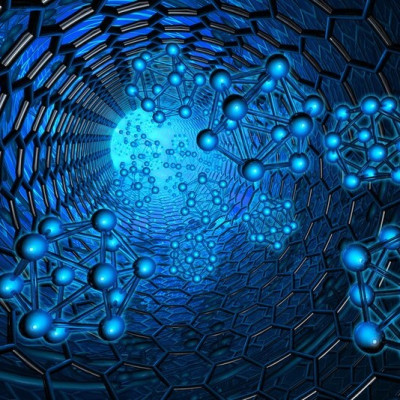

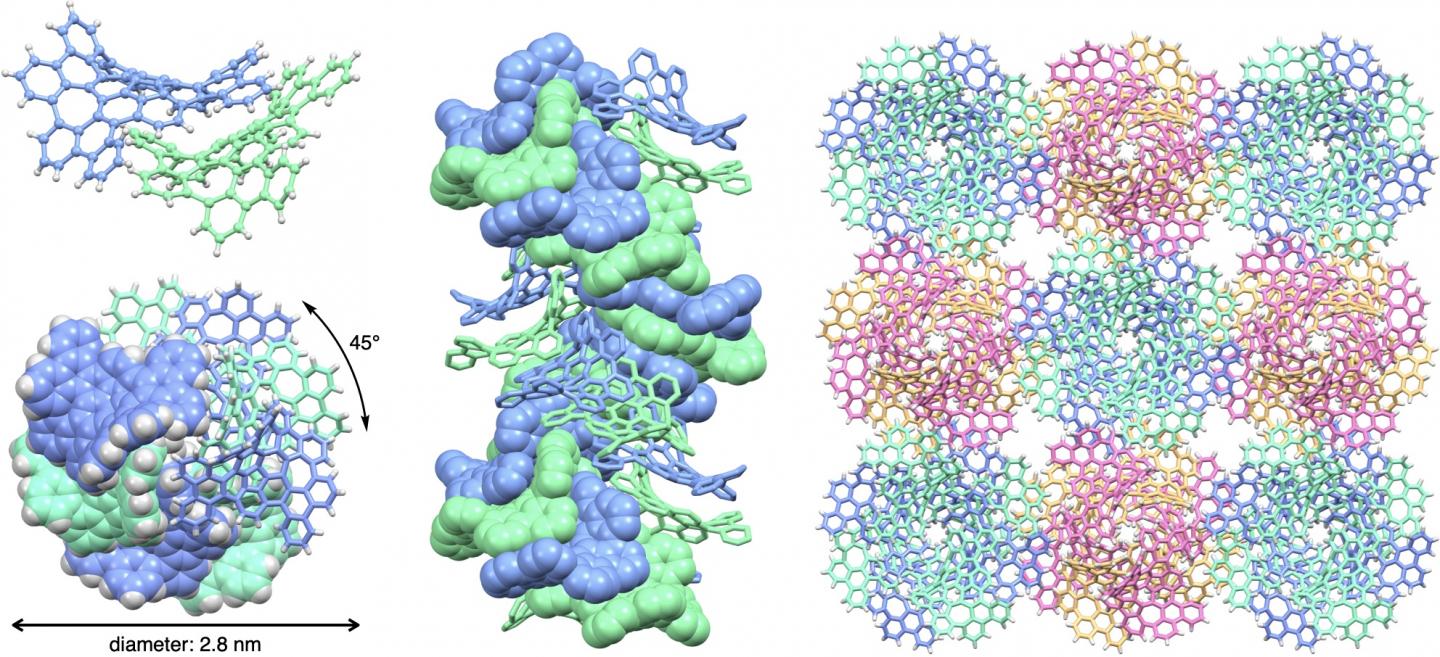

Structure of double-helix supramolecular nanofibers assembled from 'bitten' warped nanographenes (bWNG). (Upper left) An assembly of two bWNGs. (Lower left) Top view of a nanofiber. A double-helix with a diameter of 2.8 nm is formed with each molecule shifted by 45 degrees. (Middle) Side view of a nanofiber. (Right) Nanofiber bundles.

"We attempted recrystallizing many times to determine the structure, but it grew to only a few hundred nanometers," Segawa said, noting that this size is much too small for X-ray crystallography. "It was only by electron diffraction, a new method for determining the structure of organic materials, that we were able to analyze the structure."

Electron diffraction is similar to X-ray crystallography, but it uses electrons instead of X-rays, resulting in a pattern of interference with the sample material that indicates the internal structure.

They found that the bWNG gel consisted of double-stranded, double-helix nanofibers that assembled themselves from curved, stackable nanographenes.

"The structure of the nanofibers is a double-stranded double helix, which is very stable and, therefore, strong," Segawa said. "Next, we would like to realize a semiconductor wire made entirely of carbon atoms."

Read the original article on EurekAlert.