A research team from the University of Nottingham have designed a new type of catalyst that combines features that are previously thought to be mutually exclusive and developed a process to fabricate nanoclusters of metals on a mass scale.

In their new research, published today in Nature Communications, they demonstrate that the behaviour of nanoclusters of palladium do not conform to the orthodox characteristics that define catalysts as either homogeneous or heterogenous.

Traditionally, catalysts are divided into homogeneous, when catalytic centres are intimately mixed with reactant molecules, and heterogenous, where reactions take place on surface of a catalyst. Usually, chemists must make compromises when choosing one type or another, as homogeneous catalysts are more selective and active, and heterogenous catalysts are more durable and reusable. However, the nanoclusters of palladium atoms appear to defy the traditional categories, as demonstrated by studying their catalytic behaviour in the reaction of cyclopropanation of styrene.

Catalysts enable nearly 80 % of industrial chemical processes that deliver the most vital ingredients of our economy, from materials (such as polymers) and pharmaceuticals right through to agrochemicals including fertilisers and crop protection. The high demand for catalysts means that global supplies of many useful metals, including gold, platinum and palladium, are become rapidly depleted. The challenge is to utilise each-and-every atom to its maximum potential. Exploitation of metals in the form of nanoclusters is one of the most powerful strategies for increasing the active surface area available for catalysis. Moreover, when the dimensions of nanoclusters break through the nanometre scale, the properties of the metal can change drastically, leading to new phenomena otherwise inaccessible at the macroscale.

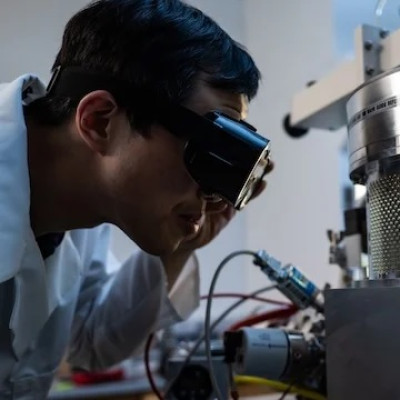

The research team used analytical and imaging techniques to probe the structure, dynamics, and chemical properties of the nanoclusters, to reveal the inner workings of this unusual catalyst at the atomic level.

The team’s discovery holds the key to unlock full potential of catalysis in chemistry, leading to new ways of making and using molecules in the most atom-efficient and energy-resilient ways.

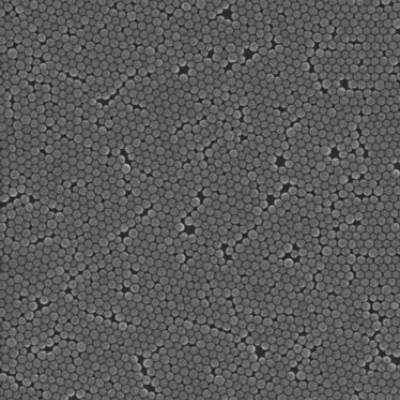

The research was led by Dr Jesum Alves Fernandes from the School of Chemistry, Propulsion Futures Beacon Nottingham Research Fellow, led the research, he said: “We use the most direct way to make nanoclusters, by simply kicking out the atoms from bulk metal by a beam of fast ions of argon – a method called magnetron sputtering. Usually, this method is used for making coatings or films, but we tuned it to produce metal nanoclusters that can be deposited on almost any surface. Importantly, the nanocluster size can be controlled precisely by experimental parameters, from single atom to a few nanometres, so that an array of uniform nanoclusters can be generated on demand within seconds.”

Dr Andreas Weilhard, a Green Chemicals Beacon postdoc researcher in the team added: “Metal clusters surfaces produced by this method are completely ‘naked’, and thus highly active and accessible for chemical reactions leading to high catalytic activity.”

The University is set to embark on a large-scale project to expand on this work with research which will lead to the protection of endangered elements. ‘Metal Atoms on Surfaces & Interfaces (MASI) for Sustainable Future’ is funded by the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and will be launched at four UK universities (Nottingham, Cardiff, Cambridge, Birmingham).

Metal nanoclusters are activated for reactions with molecules, that can be driven by heat, light or electric potential, while tuneable interactions with support materials provide durability and reusability of catalysts. In particular, MASI catalysts will be applied for the activation of hard-to-crack molecules (e.g. N2, H2 and CO2) in reactions that constitute the backbone of the chemical industry, such as the Haber-Bosch process.

Read the original article on University of Nottingham.