The health and environmental risks of these very fine particles are still unknown, but microplastic pollution is a growing global concern on land, in the seas, and in human bodies. The research is the first to identify this new source of microplastic contamination.

“Babies are the most sensitive group for any contaminants, not only microplastics (< 5 mm by definition),” says Baoshan Xing, professor of environmental and soil chemistry and director of the UMass Amherst Stockbridge School of Agriculture and co-corresponding author of the research, published in the high-impact journal Nature Nanotechnology. “Conventional techniques are unable to detect these small particles, and the smaller the particles, the larger the physiological effect.”

Xing collaborated with lead author Yu Su and co-corresponding author Rong Ji, both environmental scientists in Nanjing University’s School of the Environment, as well as other colleagues in China.

“Silicone rubber was considered to be a thermally stable polymeric material in the past, but we noticed that it undergoes aging after repeated moist heat disinfections,” Su says. “The aging and decomposition of plastics are a major source of microplastics in the environment. We proposed and confirmed that silicone rubber can be decomposed by moist heating to microplastics, even nanoplastics (< 1 µm).”

Previous research by Xing, who has been named to an annual list of the world’s most highly cited researchers every year since the analytics began in 2014, and colleagues in China showed that nanoplastics – known to widely pollute oceans, surface waters and lands – are internalized by plants and also reduce lipid digestion in a simulated human gastrointestinal system.

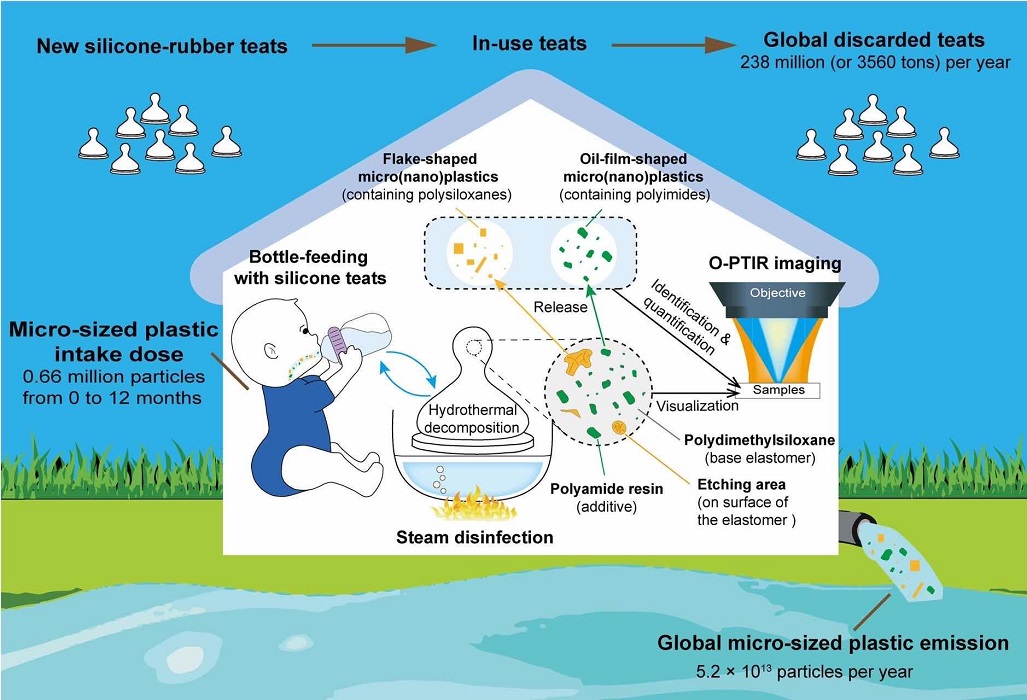

Traditional techniques are unable to detect particles smaller than about 20 micrometers, which is roughly half the size of a human hair’s thickness. At Nanjing University, researchers examined the rubber nipples using optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) microspectroscopy, the new and emerging technique that is able to analyze a material’s composition and morphology.

The research into the breakdown and pollution of silicone-rubber baby bottle nipples is highlighted in this illustration.

The microspectroscope revealed numerous flake- or oil-film-shaped micro- and nanoplastics as small as 0.6 micrometers, or 600 nanometers, in the wash waters of the steam-disinfected rubber nipples. The technique also showed submicrometer-resolved steam etching on and chemical modification of the nipple surface.

“The results indicated that by the age of one year, a baby could ingest >0.66 million elastomer-derived micro-sized plastics (MPs)…. Global MP emission from teat disinfection may be as high as 5.2 × 1013 particles per year,” the research paper states.

Xing and colleagues point out that similar silicone-rubbed-based consumer products, including bakeware and sealing rings in cups and cooking appliances, are also likely to produce micro- and nanoplastic particles when heated at or above 100 degrees C. They will continue their research into the release of particles into the environment from various plastic objects.

“We’ve identified this significant new source of microplastics to the environment,” Xing says. “Some plastics go into the sewer systems. They get into the water and landfills. They have such a long lifetime in the environment because they don’t decompose readily.”

Rong Ji, of Nanjing University, adds, “The behaviors of these silicon rubber-derived micro- and nanoplastics in the environment are unclear. Further research is needed to clarify their potential risks to both humans and the environment.”

Read the original article on University of Massachusetts Amherst.