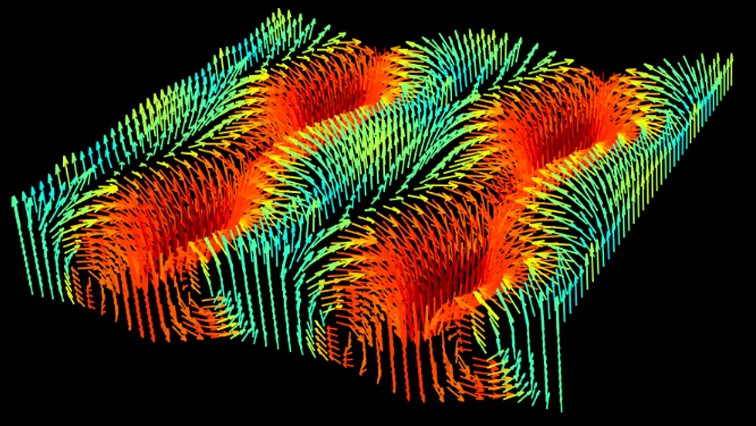

Ferromagnetic materials have a self-generating magnetic field, ferroelectric materials generate their own electrical field. Although electric and magnetic fields are related, physics tells us that they are very different classes of material. Now the discovery by University of Warwick-led scientists of a complex electrical ‘vortex’-like pattern that mirrors its magnetic counterpart suggests that they could actually be two sides of the same coin.

Detailed in a new study for the journal Nature, funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation, and the Royal Society, the results give the first evidence of a process in ferroelectric materials comparable to the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in ferromagnets. This particular interaction plays a pivotal role in stabilising topological magnetic structures, such as skyrmions, and it might be crucial for potential new electronic technologies exploiting their electrical analogues.

Bulk ferroelectric crystals have been used for many years in a range of technologies including sonar, audio transducers and actuators. All these technologies exploit the intrinsic electric dipoles and their inter-relationship between the material’s crystal structure and applied fields.

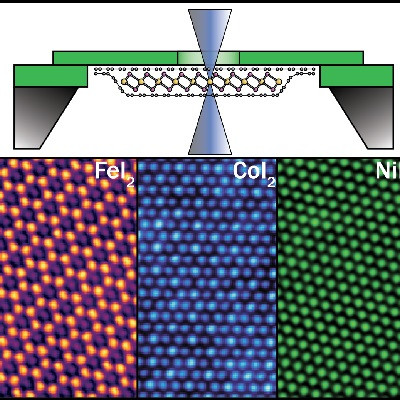

For this study, the scientists created a thin film of the ferroelectric lead titanate sandwiched between layers of the ferromagnet strontium ruthenate, each about 4 nanometres thick - only twice the thickness of a single strand of DNA.

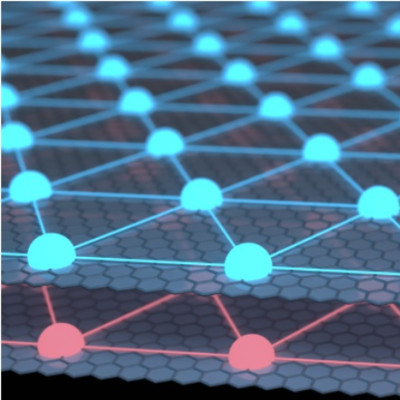

While the atoms of the two materials form a single continuous crystal structure, in the ferroelectric lead titanate layer the electric polarisation would normally form multiple ‘domains’, like a honeycomb. These domains can only be observed using state-of-the-art transmission electron microscopy and x-ray scattering.

But when the University of Warwick team examined the structure of the combined layers, they saw that the domains in the lead titanate were a complex topological structure of lines of vortexes, spinning alternately in different directions.

Almost identical behaviour has also been seen in ferromagnets where it is known to be generated by the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMi).

Lead author Professor Marin Alexe of the University of Warwick Department of Physics said: “If you look at how these characteristics scale down, the difference between ferromagnetism and ferroelectricity becomes less and less important. It might be that they will merge at some point in one unique material. This could be artificial and combine very small ferromagnets and ferroelectrics to take advantage of these topological features. It’s very clear to me that we are at the tip of the iceberg as far as where this research is going to go.”

Co-author Dorin Rusu, a postgraduate student at the University of Warwick, said: “Realising that in ferroelectrics dipolar textures that mimic their magnetic counterpart to such a degree ensures further research into the fundamental physics that drives such similarities. This result is not a trivial matter when you consider the difference in the origin and strengths of the electric and magnetic fields.”

The existence of these vortexes had previously been theorised, but it took the use of cutting-edge transmission electron microscopes at the University of Warwick, as well as the use of synchrotrons at four other facilities, to accurately observe them. These techniques allowed the scientists to measure the position of every atom to a high degree of certainty.

Read the original article on University of Warwick.