“A real solution is not provided to the patient,” said Maria Clara Labonia, a medical doctor and Ph.D. student at the University of Utrecht, in the Netherlands, who is the lead author of the study. “So many aims are towards new therapeutic strategies.”

“You have a temporary boost of proliferation in the heart muscle cells—and then get the hell out and just leave them alone, because they need to become mature again.”

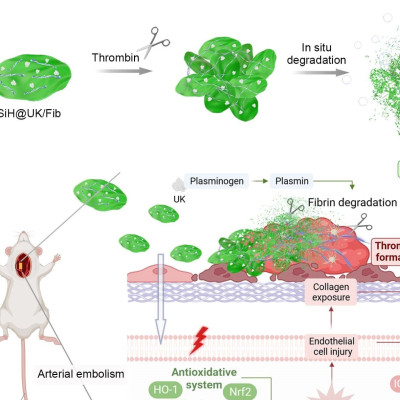

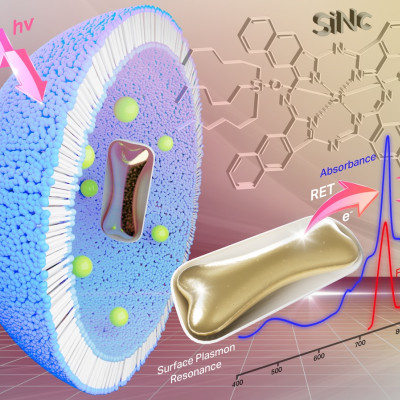

Labonia and her colleagues aim to use technology much like the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines to help the body repair damaged heart cells. Like the vaccines, the primary agent in this therapy is modified messenger RNA—genetic material that provides instructions to make proteins—encased by tiny shells of fat (called lipid nanoparticles) that protect the RNA from being immediately destroyed by the body. Unlike a vaccine, the treatment would work by instructing the heart’s cells to repair themselves after they are damaged by a heart attack. For this preliminary study, researchers tried to get the mRNA-laden nanoparticles to heart cells.

They found that after 24 hours, the mRNA did reach its destination, although more had reached liver and spleen cells. Labonia said this was expected, since the liver usually processes the fats that the lipid nanoparticles are made of. Nevertheless, the fact that the mRNA did produce proteins in heart cells means the approach could work for a treatment, said Labonia.

“That’s what keeps me motivated to continue with this project,” she said. Her next step will be to replace the “reporter” mRNA, which produces glowing proteins, with mRNA that serve a therapeutic purpose.

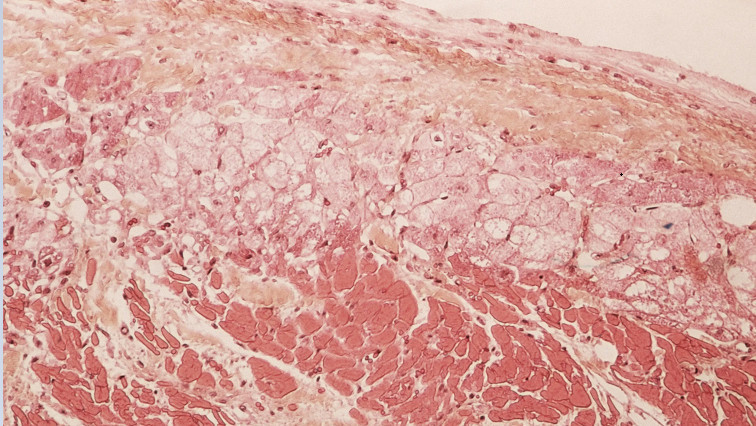

Other research has already gone further in testing similar approaches. In a study led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and published in January in the journal Science, researchers used mRNA to produce so-called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells inside the body to treat cardiac fibrosis, which is the stiffening and scarring of the heart during heart disease. CAR-T cells are more typically used in cancer treatment to try to get a patient’s own immune system to attack cancer cells. In this case, the CAR-T cells would target cardiac fibroblasts, which produce the heart’s connective tissue and become overactive after heart injury, causing fibrosis.

“We actually resolved that fibrosis by using…this technique,” said Hamideh Parhiz, a research assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania and an author of the study. She also said that heart function improved in mice whose heart injuries were treated using the therapy. Some of the treated mice’s hearts were nearly identical to those with no heart injury.

Using mRNA to produce CAR-T cells is an ideal approach, said Parhiz, since mRNA does not last long in the body, producing a temporary effect. Permanently targeting active fibroblasts would cause problems, since they are normally a healthy part of wound healing.

The temporary nature of RNA is an important part of what makes it a useful way to treat heart injury. In a 2021 study, researchers injected mice with a different kind of RNA, called microRNA, which caused the mice to regenerate heart cells after injury from a heart attack. These tiny RNA block a host of mRNA that would normally produce proteins, setting off a process that convinces the body to produce new heart cells, which doesn’t usually happen in adults. That effect can’t be permanent because it could cause uncontrolled cell growth—in other words, cancer. Particularly if the RNA got to cells other than heart cells.

“You have a temporary boost of proliferation in the heart muscle cells, and then [you] get the hell out and just leave them alone, because they need to become mature again,” said Leon de Windt, a professor of molecular cardiovascular biology at Maastricht University and an author of the study.

Though all three approaches to treating heart injury are still in the early phases of testing, they show promise in treating heart damage that would otherwise be permanent. Labonia says that mRNA treatments are not limited to heart injury—they could be useful for treating cancers and genetic diseases as well as for protein replacement therapy.

“There are many possibilities there,” she said. “It’s a hot topic right now.”

Read the original article on IEEE Spectrum.