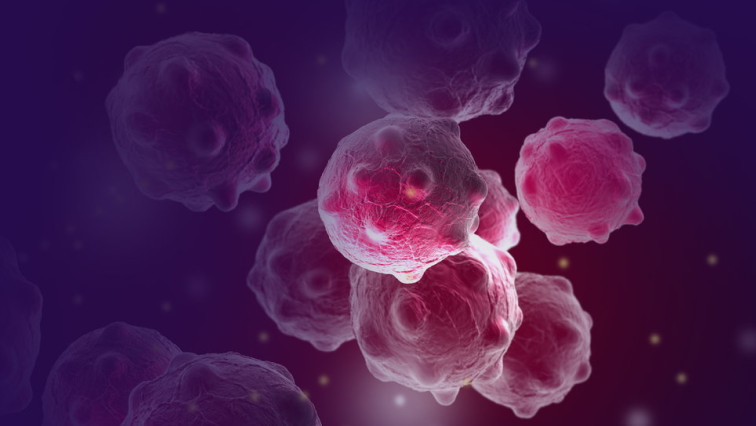

Eugenia Kharlampieva, Ph.D., and Eddy Yang, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Alabama at Birmingham have demonstrated a 100-nanometer polymersome that safely and efficiently carries PARP1 siRNA to triple-negative breast cancer tumors in mice. There, the siRNA knocked down expression of the DNA repair enzyme PARP1 and, remarkably, gave breast cancer-bearing mice a fourfold increase in survival.

PARP inhibitors have been successful in targeting tumors with defects in DNA repair and may modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment. However, due to bone marrow suppression, it has been challenging to combine many of the PARP inhibitors with chemotherapy. Specifically targeting PARP1 in the tumor may allow for novel combination treatments.

“To the best of our knowledge, our work represents the first example of biodegradable, non-ionic polymeric nanovesicles capable of efficiently encapsulating and delivering PARP1 siRNA to knock down PARP1 in vivo,” they report in the journal ACS Applied Bio Materials. “Our study provides an advanced platform for developing precision-targeted therapeutic carriers, which could help develop effective drug delivery nanocarriers for breast cancer gene therapy.”

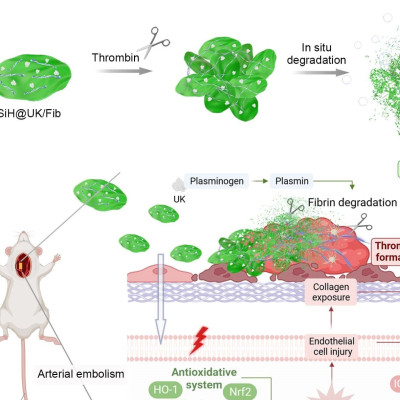

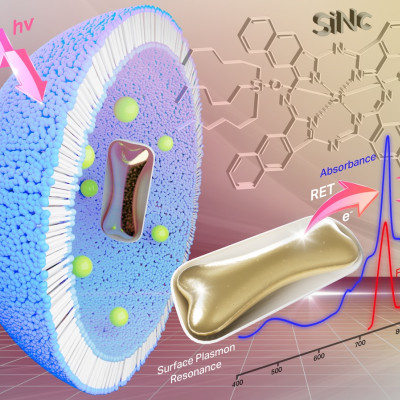

Their fast and safe approach for the PARP1 siRNA encapsulation and delivery to breast cancer cells uses polymeric nanovesicles assembled from three biodegradable block copolymers linked together in a straight chain. The first block, a chain of 14 molecules of N-vinylpyrrolidone, is linked to the second block, a chain of 47 molecules of dimethylsiloxane, and that is linked to a third block of another 14-molecule chain of N-vinylpyrrolidone.

The UAB researchers used straightforward methods that allow these block polymers to assemble into 100 nanometer-diameter, hollow-sphere polymersomes that have a robust shell thickness of about 13 nanometers. The assembly method is capable of large-scale production and consistent quality control.

Polymersomes assembled in the presence of one micromolar PARP1 siRNA were able to load the RNA inside the nanocarriers. When these were broken open by ultrasound in vitro, the siRNA was released unchanged. The polymersomes could also be loaded with Cy5.5 fluorescent dye; 18 hours after injection of the dye-loaded nanocarriers into tumor-bearing mice, dye had accumulated in the tumors through passive targeting.

siRNA-loaded polymersomes were tested with HER2-positive, trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells in culture. They reduced protein levels of PARP1 in the cells, which inhibited their proliferation and suppressed the NF-κB transcription factor pathway, similar to what the researchers previously reported using PARP inhibitors.

Researchers were also able to attach fluorescent dye covalently to the outside of these versatile nanocapsules, and they suggest that targeting molecules can be added the same way to make the polymersome home in to a tumor.

“These non-ionic, biodegradable PVPON14−PDMS47−PVPON14 nanovesicles capable of the efficient encapsulation and delivery of PARP1 siRNA to successfully knock down PARP1 in vivo have strong potential to become an advanced platform for the development of precision-targeted therapeutic carriers,” Yang said. “They could help in the development of highly effective drug delivery nanocarriers for breast cancer gene therapy.”

PVPON is poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone), and PDMS is poly(dimethylsiloxane). The siRNAs the polymersomes can carry are very small, about 21 to 25 nucleotides long, yet they can specifically inhibit oncogene expression through degradation of its messenger RNA.

Read the original article on The University of Alabama at Birmingham.