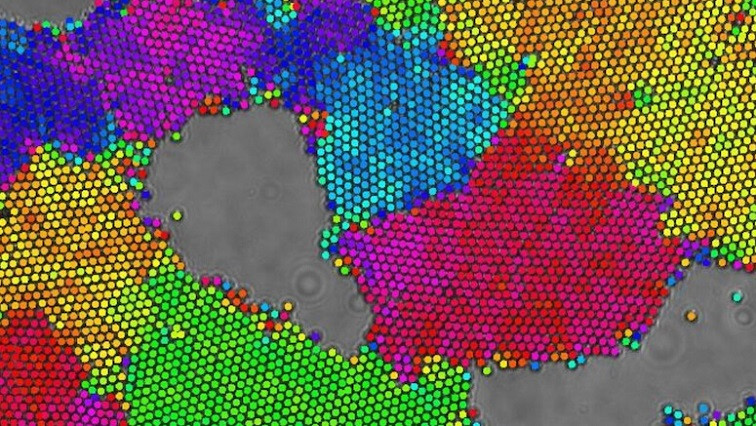

That the boundaries can change so readily was not entirely a surprise to the researchers, who used spinning arrays of magnetic particles to view what they suspect happens at the interface between misaligned crystal domains.

According to Sibani Lisa Biswal, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering, and graduate student and lead author Dana Lobmeyer, interfacial shear at the crystal-void boundary can indeed drive how microstructures evolve.

The technique reported in Science Advances could help engineers design new and improved materials.

To the naked eye, common metals, ceramics and semiconductors appear uniform and solid. But at the molecular scale, these materials are polycrystalline, separated by defects known as grain boundaries. The organization of these polycrystalline aggregates govern such properties as conductivity and strength.

Under applied stress, grain boundaries can form, reconfigure or even disappear entirely to accommodate new conditions. Even though colloidal crystals have been used as model systems to see boundaries move, controlling their phase transitions has been challenging.

“What sets our study apart is that in the majority of colloidal crystal studies, the grain boundaries form and remain stationary,” Lobmeyer said. “They’re essentially set in stone. But with our rotating magnetic field, the grain boundaries are dynamic and we can watch their motion.”

In experiments, the researchers induced colloids of paramagnetic particles to form 2D polycrystalline structures by spinning them with magnetic fields. As recently shown in a previous study, this type of system is well suited for visualizing phase transitions characteristic of atomic systems.

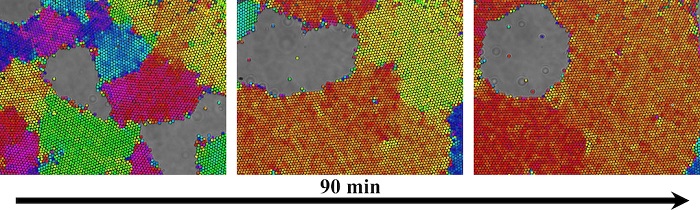

Here, they saw that gas and solid phases can coexist, resulting in polycrystalline structures that include particle-free regions. They showed these voids act as sources and sinks for the movement of grain boundaries.

In a Rice University study, a polycrystalline material spinning in a magnetic field reconfigures as grain boundaries appear and disappear due to circulation at the interface of the voids. The various colors identify the crystal orientation.

The new study also demonstrates how their system follows the long-standing Read-Shockley theory of hard condensed matter that predicts the misorientation angles and energies of low-angle grain boundaries, those characterized by a small misalignment between adjacent crystals.

By applying a magnetic field on the colloidal particles, Lobmeyer prompted the iron oxide-embedded polystyrene particles to assemble and watched as the crystals formed grain boundaries.

“We typically started out with many relatively small crystals,” she said. “After some time, the grain boundaries began to disappear, so we thought it might lead to a single, perfect crystal.”

Instead, new grain boundaries formed due to shear at the void interface. Similar to polycrystalline materials, these followed the misorientation angle and energy predictions made by Read and Shockley more than 70 years ago.

“Grain boundaries have a significant impact on the properties of materials, so understanding how voids can be used to control crystalline materials offers us new ways to design them,” Biswal said. “Our next step is to use this tunable colloidal system to study annealing, a process that involves multiple heating and cooling cycles to remove defects within crystalline materials.”

The National Science Foundation (1705703) supported the research. Biswal is the William M. McCardell Professor in Chemical Engineering, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering.

Read the original article on Rice University.