“This is important because the earlier growers can identify plant diseases or fungal infections, the better able they will be to limit the spread of the disease and preserve their crop,” says Qingshan Wei, corresponding author of a paper on the work and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State.

“In addition, the more quickly growers can identify abiotic stresses, such as irrigation water contaminated by saltwater intrusion, the better able they will be to address relevant challenges and improve crop yield.”

The technology builds on a previous prototype patch, which detected plant disease by monitoring volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by plants. Plants emit different combinations of VOCs under different circumstances. By targeting VOCs that are relevant to specific diseases or plant stress, the sensors can alert users to specific problems.

“The new patches incorporate additional sensors, allowing them to monitor temperature, environmental humidity, and the amount of moisture being ‘exhaled’ by the plants via their leaves,” says Yong Zhu, co-corresponding author of the paper and Andrew A. Adams Distinguished Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at NC State.

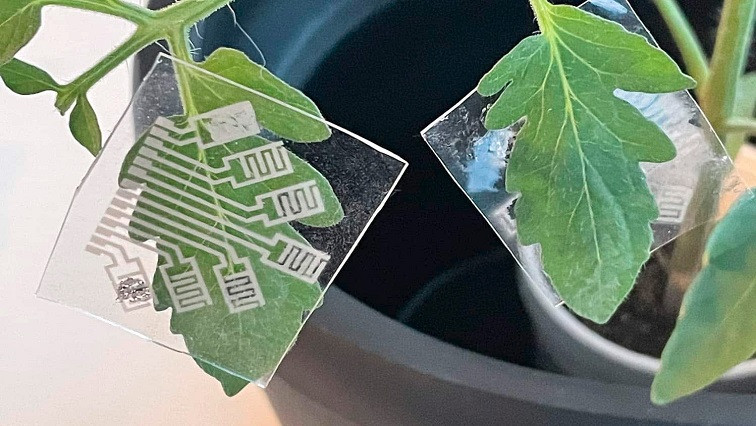

The patches themselves are small – only 30 millimeters long – and consist of a flexible material containing sensors and silver nanowire-based electrodes. The patches are placed on the underside of leaves, which have a higher density of stomata – the pores that allow the plant to “breathe” by exchanging gases with the environment.

The researchers tested the new patches on tomato plants in greenhouses, and experimented with patches that incorporated different combinations of sensors. The tomato plants were infected with three different pathogens: tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV); early blight, which is a fungal infection; and late blight, which is a type of pathogen called an oomycete. The plants were also exposed to a variety of abiotic stresses, such as overwatering, drought conditions, lack of light, and high salt concentrations in the water.

The researchers took data from these experiments and plugged them into an artificial intelligence program to determine which combinations of sensors worked most effectively to identify both disease and abiotic stress.

“Our results for detecting all of these challenges were promising across the board,” Wei says. “For example, we found that using a combination of three sensors on a patch, we were able to detect TSWV four days after the plants were first infected. This is a significant advantage, since tomatoes don’t normally begin to show any physical symptoms of TSWV for 10-14 days.”

The researchers say they are two steps away from having a patch that growers can use. First, they need to make the patches wireless – a relatively simple challenge. Second, they need to test the patches in the field, outside of greenhouses, to ensure the patches will work under real-world conditions.

“We’re currently looking for industry and agriculture partners to help us move forward with developing and testing this technology,” Zhu says. “This could be a significant advance to help growers prevent small problems from becoming big ones, and help us address food security challenges in a meaningful way.”

The paper, “Abaxial leaf surface-mounted multimodal wearable sensor for continuous plant physiology monitoring,” is published in the open-access journal Science Advances.

The work stems from the Emerging Plant Disease and Global Food Security research cluster at NC State. This interdisciplinary program is focused on developing new knowledge and tools to better understand and counter emerging infectious plant diseases.

Read the original article on North Carolina State University.