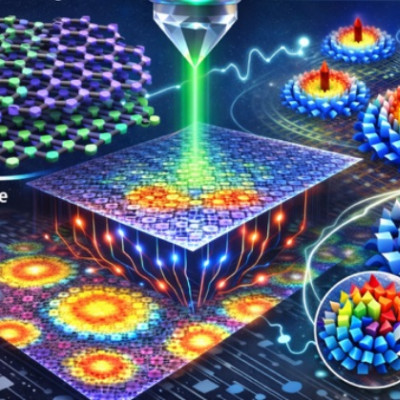

2D materials have physical properties that are not shared by bulk material. The confinement of charge carriers is one reason for this. There are two ways to produce these 2D materials: exfoliating a larger crystal or growing a 2D layer. Exfoliation means peeling off layers from a larger crystal until you are left with just one layer. ‘This process is time-consuming and requires specific skills and equipment,’ says Antonija Grubisic-Cabo, a surface scientist at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) and first author of the Advanced Science paper. ‘Furthermore, it often results in very small flakes, while the adhesive tape that is used can leave polymers on their surfaces.’

Gold

Growing 2D films is another approach. This allows the production of large samples under controlled conditions. ‘However, it often takes a lot of time to work out how to grow such 2D materials. And the process doesn’t always result in a perfect layer,’ says Grubisic-Cabo. Together with last author Maciej Dendzik, she assembled a ‘dream team’ of colleagues, many of whom had previously worked together at Aarhus University (Denmark) as PhD students, to develop a simple technique for the production of 2D materials.

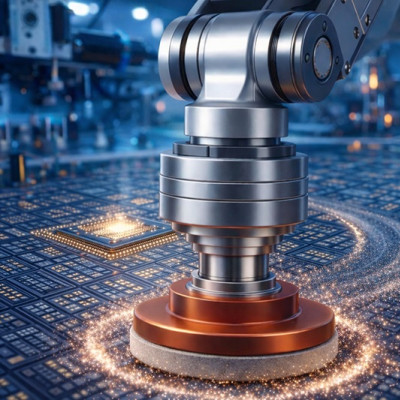

‘We knew of some experiments in which gold films were used to exfoliate bulk material. But these were mainly performed in air which means that this technique is not very suitable for air-sensitive materials, or for surface science research.’ The team wanted a technique that would allow production of air-sensitive 2D materials on a range of substrates. In their first attempt, they used a gold crystal in a high vacuum chamber. ‘We basically slammed the crystal on bulk material and discovered that a nice 2D layer stuck to the gold.’ Why this happens is not yet clear, but the team suspects that the bond with the gold is stronger than the Van der Waals force that keeps the layers in the bulk crystal together.

Devices

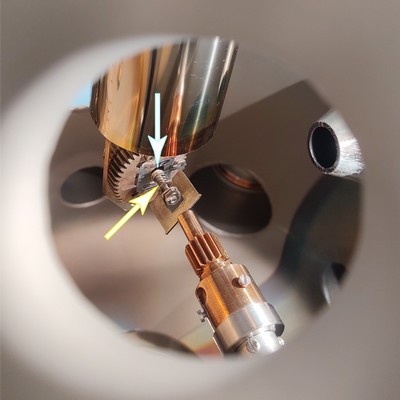

They have built on this first experiment, adding a spring to the stage with the bulk material which acts as a shock absorber and thus allows better control of the impact of the gold crystal. Furthermore, the team showed that both silver and the semiconductor germanium could be used as a substrate to peel off 2D materials. ‘Gold crystals are a standard feature in surface science labs, where they are used in the calibration of instruments, for example. Scientists don’t like to damage these crystals, but that didn’t happen in these experiments,’ says Grubisic-Cabo. ‘And we have since changed the protocol to use single crystal gold thin films. This has the added advantage of being able to dissolve the gold so that we can isolate the 2D sample, as long as it is stable in air or liquid.’

This image shows the set-up for kinetic in situ single-layer synthesis (KISS). The bulk material is placed on a sample holder with a spring to regulate the impact (yellow arrow). It is then pressed against the gold crystal (the slightly brighter ring below the blue arrow). After release, a 2D layer will be attached to the gold substrate.

These isolated samples may be used for the next stage: building devices from the 2D materials that will be produced using the KISS technique. ‘This is not yet possible, but we are working on it,’ says Grubisic-Cabo. ‘So, what we do have is a technique to produce very clean, large 2D samples in a very simple way, which allows us to create air-sensitive 2D materials. Furthermore, our technique uses standard equipment that is present in virtually every surface science laboratory.’

Read the original article on University of Groningen.