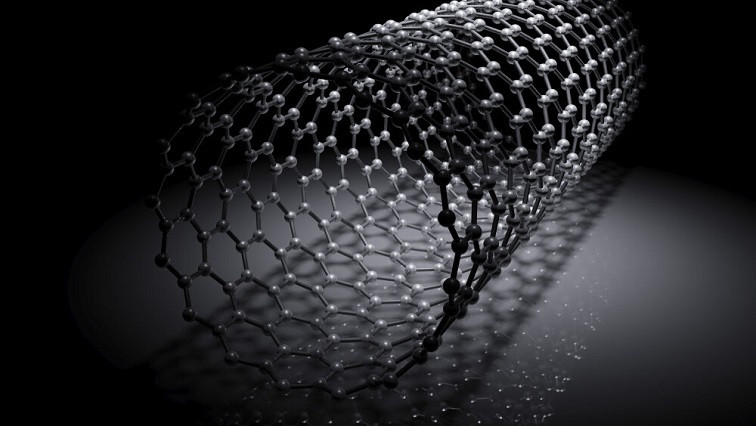

More than 5,000 tonnes of CNTs are produced annually for use in research labs and commercial industries. Due to their unique properties, CNTs are used in diverse applications such as batteries, lightweight construction materials, functional textiles, wearable devices, and increasingly in biomedical research.

“As we move toward a clean and diversified energy and materials revolution, the field of advanced materials needs a clearly defined science-based path in measurement, identification, classification and reporting throughout the entire material life cycle, from development to disposal, in order to fully scale CNTs across sectors and industries while also benefiting society and the environment,” said Rachel Meidl, fellow in energy and sustainability at Rice’s Baker Institute for Public Policy and co-author of the study published in the journal Nature Reviews Materials.

In 2019, a non-governmental organization in the European Union (EU) added carbon nanotubes to a list of chemicals that they believe “should be restricted or banned in the EU,” citing concerns from some of the many published works that studied the toxicology and environmental persistence of carbon nanotubes.

The authors of the new study investigated how carbon nanotubes have been classified chemically, given their many, diverse forms and ways to process, modify or use them. The results of toxicology and environmental studies varied widely, depending on these different carbon nanotube forms and how the studies were conducted.

“We realized that there were so many different forms of carbon nanotubes, that it seemed strange that such diverse materials could even be classified under one name,” said Daniel Heller, co-author of the study, head of the Cancer Nanomedicine Laboratory at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a Rice alumnus. “We also found that the toxicological and environmental risks of carbon nanotubes depend heavily on these differences, just like how different forms of silicon dioxide can either cause the lung disease silicosis or help keep your teeth clean as an ingredient in toothpaste.”

The authors suggest that the volume and prevalence of these materials and the nuanced and inconsistent picture of risk requires them to be more precisely classified and defined in order to identify toxicological and environmental risks. Investigators should adopt more consistent classification methods, measurement standards and consideration of potential toxicological and environmental impacts across the full life cycle of the materials that contain carbon nanotubes, including when they are used to replace more toxic or polluting materials, they said.

The authors recommend the construction of a comprehensive framework to classify, characterize and assess potential health, environmental and safety impacts of CNTs, because it would have a positive impact on both research and industry. And these tasks will provide policymakers with the data-driven tools to selectively regulate the subsets of CNTs deemed to be high risk, while ensuring that any restrictions on synthesis, production, manufacturing, use, transportation and disposal are science-based and minimally disruptive to the emerging field of carbon nanomaterials.

Additionally, transitioning to a circular carbon economy will mean that researchers will work to design out waste or use carbon-to-value pathways that deems end-of-use CNT and CNT-based products as a resource.

“Carbon nanotubes may have far fewer energy and material requirements as well as fewer environmental and social consequences than other materials, making them ideal for the energy transition,” said co-author Matteo Pasquali, the A.J. Hartsook Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and director of Rice’s Carbon Hub. “For example, they are the only credible alternative to copper and aluminum for large-scale electrification and to steel for large-scale construction.

“The toxicological studies conducted in the early days gave contrasting results and are no longer applicable to the new generation of materials, which is being made with much better control on structure, purity and macroscopic form,” he continued. “Standardizing CNT classifications is necessary to sort the wheat from the chaff, so that policymakers will be able to minimize risks to workers and consumers while also creating regulatory certainty for industry, researchers and the general public.”

The authors argue that approaching this problem from a systems perspective presents opportunities to expand the application of carbon materials in industrial, commercial and medical sectors; to support a dynamic and skilled workforce; to ensure responsible development, use and end-of-life management from lab to market; and to help the world meet global climate targets and sustainability goals.

Read the original article on Rice University.