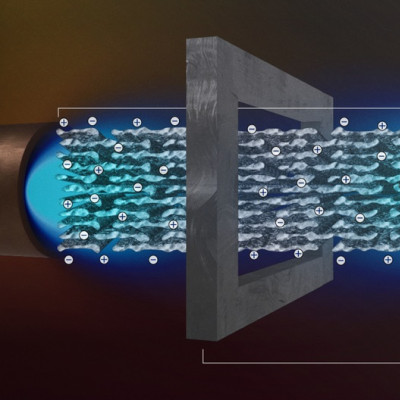

Clean drinking water is of vital importance to all people worldwide. Membranes are used to efficiently remove micropollutants, such as steroid hormones that are harmful to health and the environment. A very promising membrane material is made of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes (VaCNT). “This material is amazing – with small pores of 1.7 to 3.3 nanometers in diameter, a nearly perfect cylindrical shape, and small torsion,” says Professor Andrea Iris Schäfer, who heads KIT’s Institute for Advanced Membrane Technology (IAMT). “The nanotubes should have a highly adsorbing effect, but have a very low friction only.” Currently, pores are too large for effective retention, but smaller pores are not yet feasible technically.

Interplay of Forces

In experiments with steroid micropollutants, IAMT researchers studied why VaCNT membranes are perfect water filters. They used membranes produced by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in Livermore (California, USA). The finding: The low adsorption of VaCNT, i.e. deposition on the surface, is desirable for highly selective membranes targeting special substances.

The study reveals that adsorption in membrane nanopores does not only depend on the adsorption surface and the limited mass transfer, but also on the interplay of hydrodynamic forces, friction, and the forces of attraction and repulsion at the liquid-wall interface. Highly water-permeable nanopores exhibit low interaction due to the small friction and the high flow rate. “When the molecules are not retained because of their size, interaction with the material will often determine what happens. The molecules will bounce through the membrane similar to a climber climbing a wall. This is much easier when there are many good climbing holds,” Schäfer explains. Studies like that performed by IAMT help to specifically design pore geometry and pore surface structure.

Ten Years to Turn the Idea into an Experiment

The membranes were developed by Dr. Francesco Fornasiero and his team at LLNL. The experiments with the micropollutants were carried out and evaluated using latest analytical instruments at IAMT. “It took about ten years to turn the idea into a successful experiment that has met with the wide interest of the membrane technology community,” Schäfer says. Production of such nearly perfect membranes is extremely difficult. On larger areas of some square centimeters, the probability of defects is very high. And defects would influence the results. In recent years, LLNL succeeded in producing membranes on larger areas. In parallel, IAMT researchers built very small filtration systems for experiments to retain trace pollutants on two square centimeters. “Downscaling is extremely difficult. Having managed this together is a big success,” Schäfer says. “Now, we are waiting for the development of membranes with even smaller pores.”

The study was the first to focus on the interplay of hydrodynamic forces, friction, and forces of attraction and repulsion. It provides basic findings with respect to water processing. These may benefit ultra- and nanofiltration processes controlled by nanopores.

Read the original article on Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT).