Quantum materials have generated considerable interest for computing applications in the past several decades, but non-trivial quantum properties—like superconductivity or magnetic spin—remain fragile states.

“When designing quantum materials, the game is always a fight against disorder,” said MSE associate professor Robert Hovden.

Heat is the most common form of disorder that disrupts quantum properties. Quantum materials often only exhibit exotic phenomena at very low temperatures when the atom nearly stops vibrating, allowing the surrounding electrons to interact with one another and rearrange themselves in unexpected ways. This is why quantum computers are currently being developed in baths of liquid helium at −269 °C, or around -450 F. That's just a few degrees above zero Kelvin (-273.15 °C).

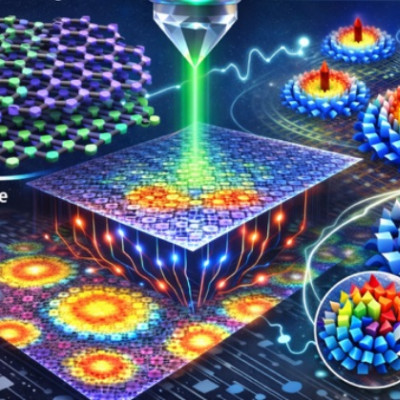

Materials can also lose quantum properties when exfoliated from 3D down to a 2D single layer of atoms, a thinness of particular interest for developing nanoscale devices.

Now a University of Michigan-led research team has developed a new way to induce and stabilize an exotic quantum phenomenon called a charge density wave at room temperature. They've essentially identified a new class of 2D materials. The results are published in Nature Communications.

“This is the first observation of a charge density wave that’s ordered and in two dimensions. We were shocked that not only does it have a charge density wave in two dimensions, but the charge density wave is greatly enhanced,” said Hovden.

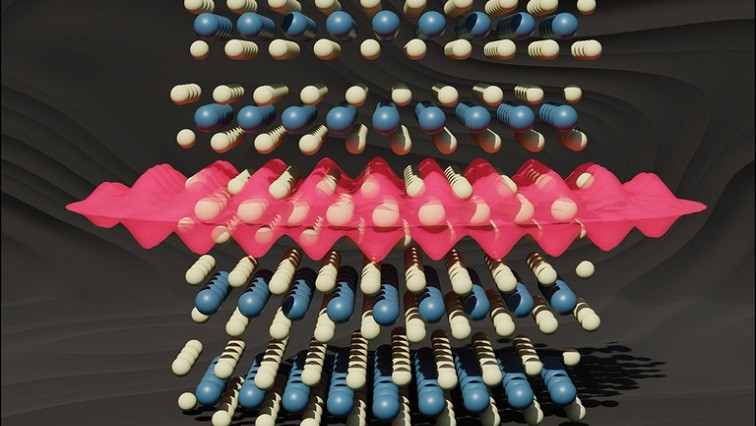

Rather than the typical approach of exfoliating and peeling off individual atomic layers to make a 2D material, the researchers grew the 2D material inside of another matrix. They dubbed the new class of materials “endotaxial” from the Greek roots “endo”, meaning within, and “taxis”, meaning in an ordered manner.

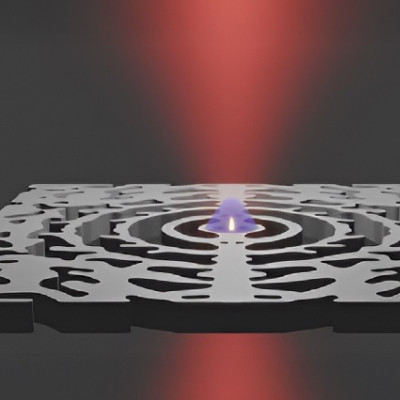

The researchers worked with a metallic crystal, tantalum disulfide (TaS2) which, like any crystal, has atoms ordered in a pattern like neatly arranged ping pong balls in all directions. They observed that as the material grew, the electrons of the sandwiched 2D TaS2 crystal layer spontaneously clumped together to form their own crystal, known as a charge crystal or a charge density wave—a repeating pattern in the distribution of electrons in a solid material.

As the electrons clump and crystallize, their movement is restricted, and the metal no longer conducts electricity well. Without changing the chemistry of the material, the charge crystal formation has converted the material from a conductor to an insulator. This exotic quantum phenomena could prove useful as a transistor in either classical or quantum computing, acting as a gate to control voltage flow.

“This opens up the idea that endotaxial synthesis could be an important strategy to stabilize fragile quantum states at normal temperature ranges that we exist in,” said Suk Hyun Sung, first author on the paper and a University of Michigan doctoral graduate and current postdoc at the Rowland Institute at Harvard University.

With a charge crystal stable at room temperature in hand, the researchers decided to heat it up to observe changes.

“It’s ordered at unexpectedly high temperatures. Not only at room temperature, but if you heat it up past the boiling point of water, it still has a charge density wave,” said Hovden.

The researchers eventually watched the charge crystal melt away while the material remained a solid, removing the quantum state.

Experiments like this advance our basic understanding of quantum materials, which is essential as researchers work to harness exotic quantum phenomena for engineering solutions.

“Quantum materials are going to disrupt both classical and quantum computing,” said Hovden.

Both fields are stuck, says Hovden. Classical computing has exhausted what silicon can do and quantum computing can currently only operate at extremely low temperatures. They need quantum materials to move forward.

For now, this research sets the groundwork for discovering new quantum materials using the endotaxial synthesis and offers promise for stabilizing quantum properties at more practical temperatures.

Experiments were conducted using the Michigan Center for Materials Characterization (MC)2 with assistance from Tao Ma and Bobby Kerns.

Read the original article on University of Michigan.