A new way to deliver drugs using a common protein could be used to develop mosaic vaccines, vaccines effective against multiple strains of a virus like Covid-19, among other medicines in a global first.

Since the mid-2000s, ferritin, a protein that manages iron in all organisms, has been used to create vaccines as well as deliver anticancer drugs and other medicines to the body. This is largely due to its high stability at room temperature, ease of production in large amounts, and its low chance of rejection by the host body. However, the protein’s unique method of self-assembly has prevented scientists from developing a universal approach for delivering a broad range of medicines, until now.

In a new study published in the nanotechnology journal Small, researchers from King’s College London, led by Dr Kourosh Ebrahimi, report a novel way to circumvent this self-assembly by copying the behaviour of viruses like HIV-1.

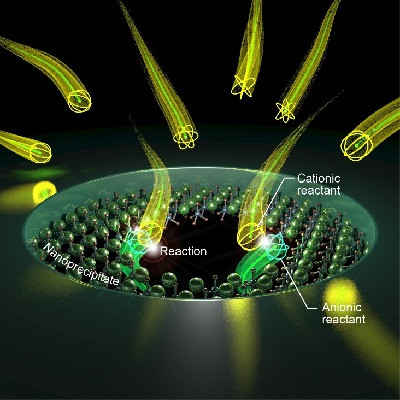

Ferritin is made up of twenty-four interlocking subunits which spontaneously self-assemble themselves to make a three-dimensional sphere that is hollow inside. The inside of these small ’nanocages’ can be filled with therapeutic drugs, but the structure of the protein needs to be broken before these are inserted within.

Traditionally, acids have been used to break open ferritin’s structure, but these methods can damage the protein's structure and do not allow the nanocages to be used with drugs that cannot be dissolved in water, like the pH-sensitive and water-insoluble anticancer treatment camptothecin.

More importantly, these traditional methods cannot be used to create multipurpose medicines like mosaic vaccines which takes antigens, the part of a vaccine which teaches the body how to fight disease, from different strains of the same virus and combines them to trigger a broader immune response.

This method has an advantage over mRNA vaccines like the recent COVID-19 vaccine, which uses messenger RNA to teach cells how to make antigens for specific diseases. As these mRNA vaccines only express part of a virus, rather than a weakened version of it like traditional vaccines, mRNA vaccines are faster to produce but may not induce a long-lasting immune response because the body doesn’t face an actual virus-like particle.

While longer lasting, the development of traditional vaccines is costly and requires many years of research and development to market a safe candidate. By introducing a ‘plug-in’ nanocage system Kourosh’s lab has now created a platform combining advantages of mRNA and traditional virus-based vaccines.

Because the virus-like nanocage platform is safe, it does not need to be clinically tested each time a different antigen is added to it, much like an mRNA platform. At the same time, different antigens can be easily plugged into the platform to create virus-like efficacious vaccines. Mimicking how viruses like HIV-1 operate, the researchers linked two of the subunits together through a string of amino acids called a peptide.

This paused ferritin’s self-assembly and opened the protein up to various water-soluble and insoluble drugs while simultaneously allowing the researchers to ’plug’ different antigens to the nanocages' surface.

The researchers have also found that this new method led to a four-fold increase in drug encapsulation for both water-soluble and -insoluble treatments. As well as delivering more drugs like doxorubicin, a widely used anticancer drug, to affected parts of the body this promises to broaden the spectrum of medicines that ferritin can carry.

The new process also hopes to open the door to a new kind of therapeutic that can simultaneously act as a vaccine, and a drug, aiming to both prevent the disease and its symptoms.

Commenting on what this meant for future treatments, Mr Yujie Sheng, a second-year PhD student in Kourosh’s lab at King’s Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and the study's first author, said, “The inability to easily control the assembly of natural protein nanocages like ferritin has been a setback for using these safe and biocompatible materials as a drug delivery system to make modern vaccines effective against multiple viruses.

“Our technology combines the benefits of mRNA technology and traditional vaccines. It is a safe platform like mRNA technology, and at the same time, different antigens can be plugged in and generate virus-like particles mimicking traditional vaccines. Additionally, using our technology, we could mix and match antigens from different viruses and create a vaccine candidate capable of training the body against multiple viruses. Such a mosaic vaccine is likely to reduce the cost and response time to future viral pandemics. We hope that the stability and ease of production presented by this platform will be recognised by pharmaceutical manufacturers.”

King’s College has been granted a patent for this technology. The lab's next step is to use their nanocage technology and develop new therapeutics against a range of diseases, such as cancer and viral infection, which they hope to research in a commercial spin-out.

Read the original article on King's College London.