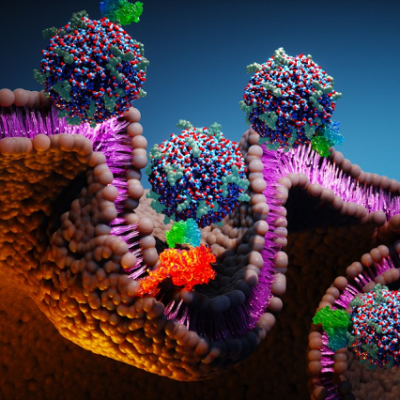

Their solution involves using nanowires to deliver therapeutic miRNA to T-cells. This new modification process retains the cells’ naïve state, which means they’ll be even better disease fighters when they’re infused back into a patient.

“By delivering miRNA in naïve T cells, we have basically prepared an infantry, ready to deploy,” Singh said. “And when these naïve cells are stimulated and activated in the presence of disease, it’s like they’ve been converted into samurais.”

Lean and Mean

Currently in adoptive T-cell therapy, the cells become stimulated and preactivated in the lab when they are modified, losing their naïve state. Singh’s new technique overcomes this limitation. The approach is described in a new study published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

“Naïve T-cells are more useful for immunotherapy because they have not yet been preactivated, which means they can be more easily manipulated to adopt desired therapeutic functions,” said Singh, the Carl Ring Family Professor in the Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.

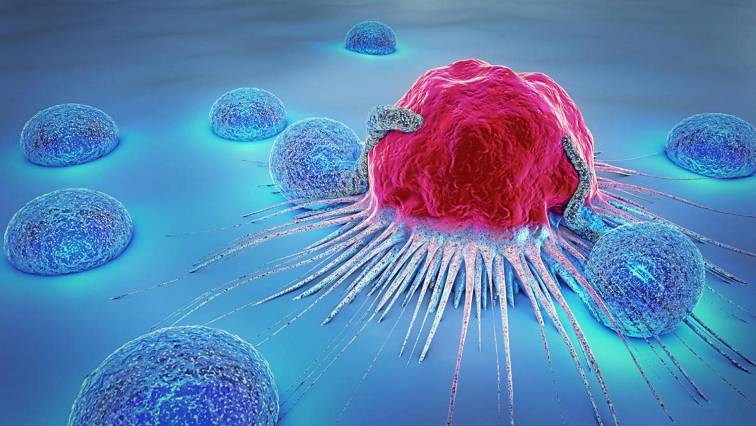

The raw recruits of the immune system, naïve T-cells are white blood cells that haven’t been tested in battle yet. But these cellular recruits are robust, impressionable, and adaptable — ready and eager for programming.

“This process creates a well-programmed naïve T-cell ideal for enhancing immune responses against specific targets, such as tumors or pathogens,” said Singh.

The precise programming naïve T-cells receive sets the foundational stage for a more successful disease fighting future, as compared to preactivated cells.

Giving Fighter Cells a Boost

Within the body, naïve T-cells become activated when they receive a danger signal from antigens, which are part of disease-causing pathogens, but they send a signal to T-cells that activate the immune system.

Adoptive T-cell therapy is used against aggressive diseases that overwhelm the body’s defense system. Scientists give the patient’s T-cells a therapeutic boost in the lab, loading them up with additional medicine and chemically preactivating them.

That’s when the cells lose their naïve state. When infused back into the patient, these modified T-cells are an effective infantry against disease — but they are prone to becoming exhausted. They aren’t samurai. Naïve T-cells, though, being the young, programmable recruits that they are, could be.

The question for Singh and his team was: How do we give cells that therapeutic boost without preactivating them, thereby losing that pristine, highly suggestable naïve state? Their answer: Nanowires.

NanoPrecision: The Pointed Solution

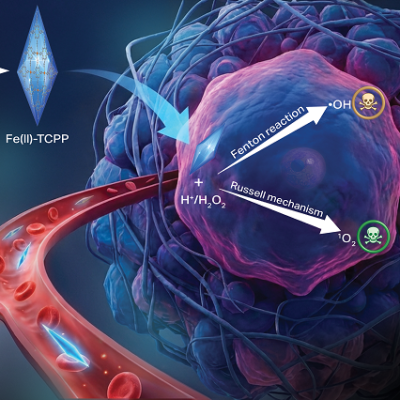

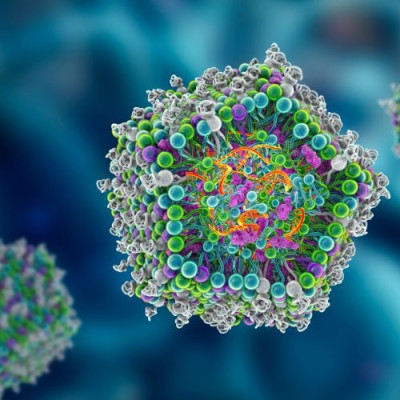

Singh wanted to enhance naïve T-cells with a dose of miRNA. miRNA is a molecule that, when used as a therapeutic, works as a kind of volume knob for genes, turning their activity up or down to keep infection and cancer in check. The miRNA for this study was developed in part by the study’s co-author, Andrew Grimson of Cornell University.

“If we could find a way to forcibly enter the cells without damaging them, we could achieve our goal to deliver the miRNA into naïve T cells without preactivating them,” Singh explained.

Traditional modification in the lab involves binding immune receptors to T-cells, enabling the uptake of miRNA or any genetic material (which results in loss of the naïve state). “But nanowires do not engage receptors and thus do not activate cells, so they retain their naïve state,” Singh said.

The nanowires, silicon wafers made with specialized tools at GeorgiaTech’s Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology, form a fine needle bed. Cells are placed on the nanowires, which easily penetrate the cells and deliver their miRNA over several hours. Then the cells with miRNA are flushed out from the tops of the nanowires, activated, eventually infused back into the patient. These programmed cells can kill enemies efficiently over an extended time period.

“We believe this approach will be a real gamechanger for adoptive immunotherapies, because we now have the ability to produce T-cells with predictable fates,” says Brian Rudd, a professor of immunology at Cornell University, and co-senior author of the study with Singh.

The researchers tested their work in two separate infectious disease animal models at Cornell for this study, and Singh described the results as “a robust performance in infection control.”

In the next phase of study, the researchers will up the ante, moving from infectious disease to test their cellular super soldiers against cancer and move toward translation to the clinical setting. New funding from the GeorgiaCTSA is supporting Singh’s research.

Read the original article on GeorgiaTech.