Backed by a $4.1 million grant from the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF), UQ’s foremost experts in stem cell technology and venom-based drug discovery are making tiny organ replicas – known as organoids - to prove the safety and efficacy of new anti-seizure treatments.

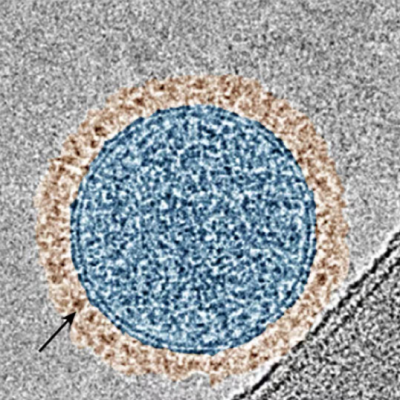

The brain organoids produced by Professor Ernst Wolvetang at the AIBN are about the size of a lentil and will be used to test novel anti-seizure spider venom peptides developed by Professor Glenn King from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience (IMB).

The safety of Professor King’s venom peptides will also be assessed in patient-derived heart cells designed by Associate Professor Nathan Palpant, also from IMB.

“Professor King’s venom-derived peptides have proven efficacy for specific types of genetic epilepsy that are in dire need of better therapeutics,” Professor Wolvetang said.

“However, testing these precision therapeutics in patients comes with significant ethical, practical and commercial implications.

An increasing number of small molecule-based anti-seizure medications are being brought to market but Professor Wolvetang says many lack specificity, effectiveness, and can lead to considerable side effects.

He says organoids grown from the stem cells of individual patients, therefore, provide researchers a unique ‘human’ canvas to develop treatments that are tailored to the specific needs of each person.

Both Professor King and Associate Professor Palpant have a strong translational track record in venom-based therapies, using a K’gari funnel web spider to develop a treatment that recently met critical benchmarks towards becoming a therapy for heart disease and stroke.

Professor King said these same spider venom peptides have also shown promise in modulating ion channels in our bodies that underlie several genetic epilepsies.

“We believe these venom peptides can be very precise, personalised drugs for specific epilepsy patients,” he said.

Associate Professor Lata Vadlamudi from UQ Centre for Clinical Research and Senior Staff Specialist in Neurology at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital said that 30 per cent of epilepsy patients do not respond to current anti-seizure medications.

“This novel approach of testing spider venom peptides in patient-specific organoids represents an exciting frontier in personalising anti-seizure medications for our epilepsy patients," she said.

Another crucial component of this research project is measuring the effectiveness of synthetic human organoids against traditional mouse models as a drug screening tool, an arm of the research project led by Professor Christoper Reid at the Florey Institute.

Professor Wolvetang said the overall project was an exercise in building the case for human stem cell-derived organoids as a tool for developing precision therapeutic approaches.

“If we are successful in showing that our organoid models are truly as predictive and as powerful as we think they are, it will be another step towards fostering regulatory change in the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and would further establish that patient specific organoids are a powerful tool that can speed up the process towards new treatments”.

Read the original article on University of Queensland.