A spoonful of sugar might actually help the medicine go down, according to recent research from the University of Mississippi. And it could reduce the harmful side effects of cancer treatment.

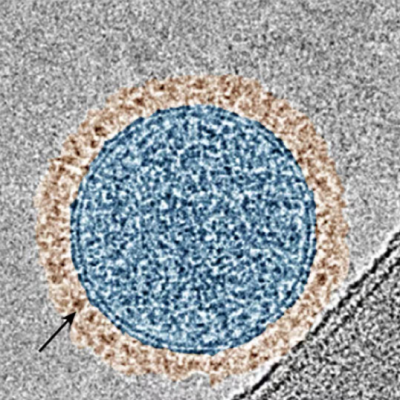

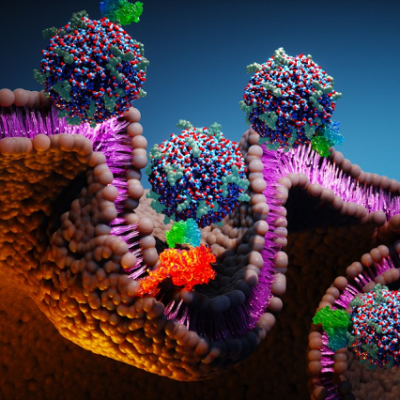

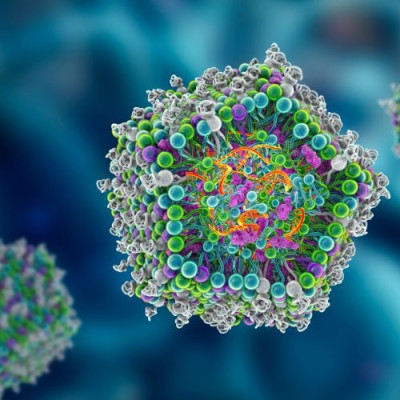

Instead of a literal spoonful of sugar, however, the researchers tried using glycopolymers – polymers made with natural sugars such as glucose – to coat tiny particles that deliver cancer-fighting medication directly to tumors. They found that glycopolymers help keep proteins from sticking to the nanoparticles, reducing the body's immune response to the treatment.

As a result, the body is better able to respond to treatment.

"The real heart of the problem is that cancer drugs are incredibly toxic," said Thomas Werfel, associate professor of biomedical engineering.

"They have a very narrow therapeutic window, meaning that the dose at which they work is very close to the dose at which they become toxic. And so as soon as you get enough dose for it to get rid of the tumor, it's also causing all this toxicity, all these off-target effects that you don't want.

"Why is that happening? That's happening because a fraction of the cancer drug gets to the cancer – in most cases, well less than 1%; over 99% goes everywhere else in the body."

That toxic medication leaking into other parts of the body can cause serious conditions such as leukemia, trigger allergic reactions and even spawn other cancers. If more of the cancer treatment reaches the tumor, however, those side effects could be reduced.

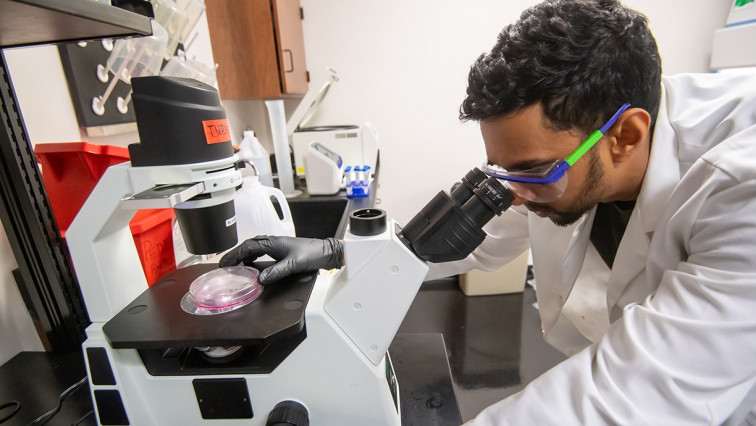

Werfel and Kenneth Hulugalla, a third-year doctoral student in biomedical engineering from Kandy, Sri Lanka, published their findings in ACS Nano in October.

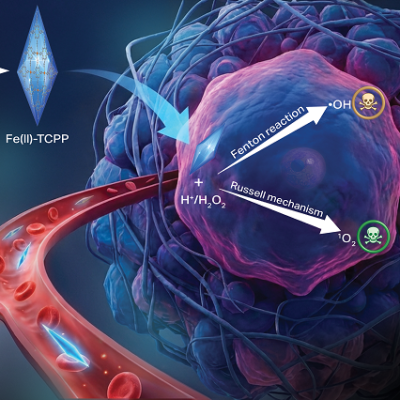

Nanoparticles – particles smaller than one-thousandth the width of a human hair – have proven to be an effective option for cancer treatment and can deliver drugs directly to tumors. But proteins – including those that trigger an immune response – tend to gather around the nanoparticles, causing the body to tag the treatment as a foreign invader.

This immune response reduces the effectiveness of the drug.

"PEG (polyethylene glycol) for the past 30 years has been the gold standard to shield these particles from that happening," Hulugalla said.

When first used, it works extremely well. But after the first time, the body's immune system can recognize and tag the drug as foreign quickly. Once that happens, the drug can't get to the tumor and work.

Glycopolymers don't have that problem, the researchers said.

"Our findings highlight that the nanoparticles we're using significantly reduce unwanted immune responses while dramatically enhancing drug delivery, both in cell and animal models," Hulugalla said. "This research could be an important step towards developing more effective cancer treatments."

Werfel and Hulugalla tested glycopolymer-coated nanoparticle treatments in mice with breast cancer and found that more nanoparticles reached the tumors in the glycopolymer treatment compared to a PEG-based particle.

The next phase of their study will include loading those nanoparticles with medication and ensuring that the product is still effective against cancer.

"One aspect of what we want to do long term is not just study this in a defensive way, but also an offensive way," Werfel said. "If we think about what we've looked at here, we've seen that the glycopolymers stimulate the immune system less.

"So, the particles stay in the body longer. They get to the tumor better. That's great.

"The other thing people have been working at for a long time is, how can we actively target the tumor? What specific signatures can we use to force more of the particle to accumulate, or more of the drug to accumulate at the tumor? That's at the forefront of our mindset for next steps."

Read the original article on University of Mississippi.