But what can be done about industries which can't eliminate their methane production? One Cambridge company thinks it has the answer – turn the gas into something else.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas made from hydrogen and carbon. It does not last as long in the atmosphere as CO2 does but it traps much more heat. About 60% of it is generated by human activity such as agriculture, the production of fossil fuels and decomposing landfill waste.

At some sites, the methane is captured and burned for energy but that still emits CO2, and so Levidian has developed a cleaner solution.

"Our Loop system uses microwave energy to split the molecules of the captured methane into carbon and hydrogen," says John Hartley, Levidian's chief executive.

"The hydrogen which is produced can be used to power factories, trucks or ships, for example. It's a clean fuel because when you burn it you get heat and energy, but there's no CO2 released – just water vapour.

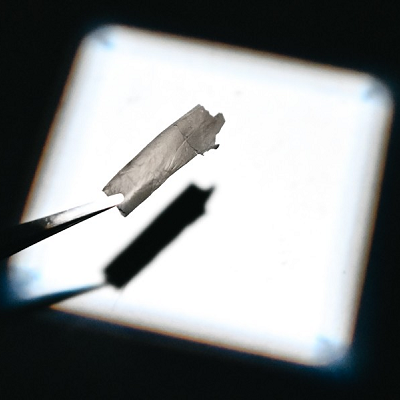

"The carbon from the methane falls into a hopper as a solid called graphene."

Graphene is the thinnest and strongest material recorded to date. It is also transparent, flexible and a good conductor for both heat and electricity.

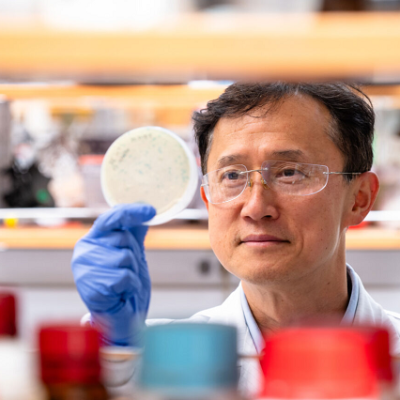

"A tiny amount of it in everyday things can make a huge difference," says Ellie Galanis. As director of commercial development, she is looking to find the most impactful applications for the graphene that Levidian harvests.

"A sprinkle in the rubber treads of tyres can make them longer-lasting, lighter and more fuel-efficient.

"We estimate that if all UK HGVs switched to these, the industry would save £300m a year in fuel.

"We've seen that by adding it to concrete you can remove some of the cement from the mix, and that's better for the environment. It can also be added to surgeons' gloves to stop them tearing. There are so many applications."

Graphene was discovered in Manchester 20 years ago but is yet to make its mark commercially.

Alistair Donaldson, Levidian's chief technology officer, said: "The biggest challenge is that no-one has been able to produce really high quality graphene in large enough quantities, but the Loop system will do that.

"We're now working with various product manufacturers and we can supply the graphene in powder, pellet or liquid form, so they can incorporate it into lots of different systems without having to change their processes. We're about to see what graphene is really capable of."

For David Reiner, professor of technology policy at Cambridge's Judge Business School, tackling methane emissions is "critical" given the government's target.

"So far we've tended to focus on technologies which produce fewer emissions, like electric cars and heat pumps, but Levidian is one of those removing emissions, and that's the harder part of the puzzle, so the government needs to find a way to incentive these types of technologies.

"To meet a 2035 target, we'll need to rely on technologies which are already a significant way down the road, because anyone having an idea now won't have time to develop and scale it. At the same time, we must still invest in new ideas because climate change doesn't end in 2035."

Levidian has already installed its Loop system at test sites around the world, including Worthy Farm, the home of Glastonbury Festival. There, it transforms methane captured from cow slurry. In the spring, it will begin a similar project with United Utilities using biogas produced by waste water treatment – a project awarded £3m of government funding.

Levidian has also developed a second generation of the Loop which is capable of processing 20 times more methane than the previous one. This will be deployed later this year.

Read the original article on BBC.