When ice melts, everything happens very quickly: as soon as the melting temperature is reached, the solid, orderly structure of the ice abruptly transforms into liquid, disordered water. Such a sudden transition is typical of the melting behaviour of all three-dimensional materials, from metals and minerals to frozen drinks.

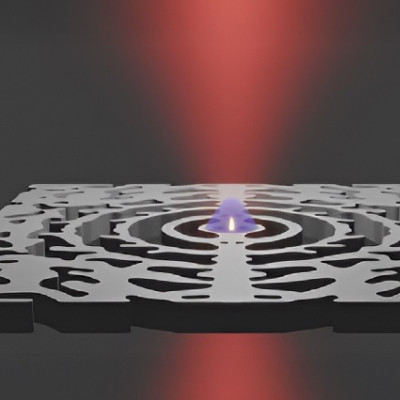

However, when a material becomes so thin that it is practically two-dimensional, the rules of melting change dramatically. Between the solid and liquid phases, a new, exotic intermediate phase of matter can arise, known as the 'hexatic phase'. First predicted in the 1970s, this hexatic phase is a strange hybrid state. The material behaves like a liquid in which the distances between the particles are irregular, but to a certain extent also like a solid, as the angles between the particles remain relatively well ordered.

Since this phase has only been observed in much larger model systems such as densely packed polystyrene balls, it remained unclear whether it could also occur in everyday covalently bonded materials. The international research team led by the University of Vienna has now succeeded in proving precisely this: the scientists were able to observe this process in atomically thin crystals of silver iodide (AgI) for the first time, thereby solving a decades-old mystery. Their findings not only confirm the existence of this elusive state in strongly bonded materials but also provide surprising new insights into the nature of melting in two dimensions.

Melting atoms in a protective 'graphene sandwich'

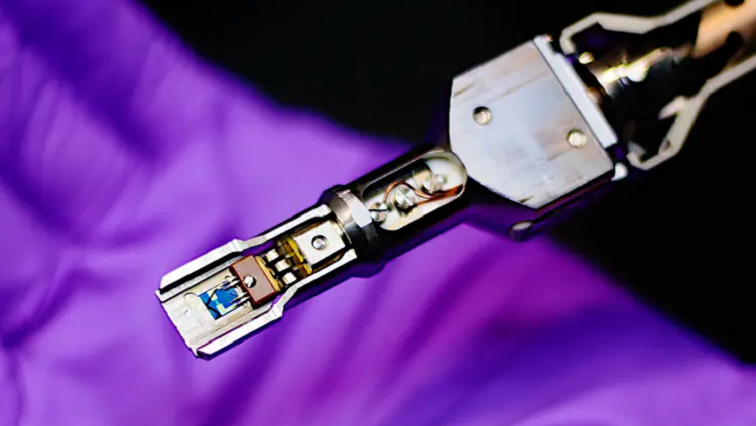

To achieve this breakthrough, the researchers developed an intriguing method to study the melting process in fragile, atomically thin crystals. They encapsulated a single layer of silver iodide between two sheets of graphene, creating a protective "sandwich" that prevented the delicate crystal from folding on to itself while allowing it to melt freely. Using a state-of-the-art scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) equipped with a heating holder, the team gradually heated the sample to over 1100 °C, filming the melting process in real time at the atomic scale.

'Without the use of AI tools such as neural networks, it would have been impossible to track all these individual atoms,' explains Kimmo Mustonen from the University of Vienna, senior author of the study. The team trained the network with huge amounts of simulated data sets before processing the thousands of high-resolution images generated by the experiment.

Their analysis yielded a remarkable result: within a narrow temperature window – approximately 25 °C below the melting point of AgI – a distinct hexatic phase occurred. Supplementary electron diffraction measurements confirmed this finding and provided strong evidence for the existence of this intermediate state in atomically thin, strongly bound materials.

A new chapter in the physics of melting

The study also revealed an unexpected twist. According to previous theories, the transitions from solid to hexatic and from hexatic to liquid should be continuous. However, the researchers observed that while the transition from solid to hexatic was indeed continuous, the transition from hexatic to liquid was abrupt, similar to the melting of ice into water. 'This suggests that melting in covalent two-dimensional crystals is far more complex than previously thought,' says David Lamprecht from the University of Vienna and the Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien), one of the main authors of the study alongside Thuy An Bui, also from the University of Vienna.

This discovery not only challenges long-standing theoretical predictions, but also opens up new perspectives in the study of materials at the atomic level. 'Kimmo and his colleagues have once again demonstrated how powerful atomic-resolution microscopy can be,' says Jani Kotakoski, head of the research group at the University of Vienna.

The results of the study not only deepen our understanding of melting in two dimensions, but also highlight the potential of advanced microscopy and AI in exploring the frontiers of materials science.

Read the original article on University of Vienna.