UTIs are among the most common bacterial infections worldwide, but inappropriate and overuse of antibiotics is driving antimicrobial resistance. Once dependable antibiotics now take longer to work or fail entirely, with clinicians having to use more potent or last-line antibiotics.

This is where targeted drug delivery – not just new drug development – becomes essential.

When an antibiotic travels throughout the body, it exposes healthy tissues and harmless bacteria to the medicine. Even low or subtherapeutic exposure encourages bacteria to adapt. At the same time, if too little of the antibiotic reaches the kidney or bladder, the infection persists, and resistance has more time to emerge.

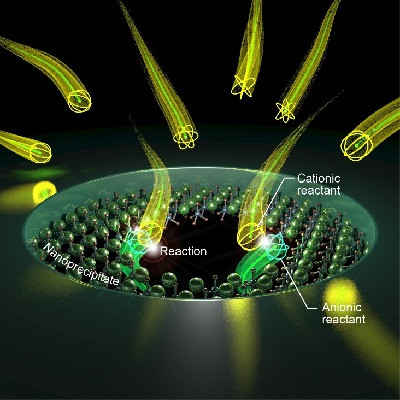

In response, PhD candidate at the Wits Advanced Drug Delivery Platform (WADDP), Atang Motaung, is engineering nanoscale particles to release the antibiotic directly into UTI-causing bacteria only. He describes the interaction as a lock-and-key mechanism, with the nanoparticle as the key and the bacterial surface as the lock.

“When they meet, the particle attaches to the bacterial cell and releases the antibiotic exactly where it is needed. Instead of flooding the entire body with medicine, the system restricts exposure to the infection site, reducing the pressures that drive resistance and improving the likelihood that the drug will work effectively,” explains Motaung.

Drug delivery is a critical component of addressing antimicrobial resistance. It controls how much antibiotic enters the body, where it travels and how many harmless bacteria it exposes in the process.

Motaung explains that globally about 60% percent of adult women will experience at least one UTI in their lifetime, and up to 30% percent will have a recurrence within six months of the first infection. As resistance grows, these cycles of recurrent infection become harder to manage, more costly for health systems, and more disruptive to patients’ daily lives.

For many patients, UTIs spread from the bladder into the kidneys, leading to upper urinary tract infections. These are far more serious and often can’t be managed with oral drugs alone; intravenous treatment is used but floods the whole body with antibiotics (the kidneys receive a fraction of the treatment), raising the likelihood of toxicity risks and the pressures that drive resistance.

Motaung’s nanoscale drug delivery system is designed for intravenous administration, but the drug’s behaviour once inside the body is expected to change significantly. A last-line antibiotic such as colistin is typically given every six hours, and half of all patients experience kidney toxicity because of the high systemic exposure. With targeted nanoparticles, the drug's release can be slowed and controlled, potentially extending the dosing interval to longer than 12 hours while delivering higher concentrations only to infected tissue.

“Although the current focus is on upper tract UTIs, the platform can be adapted to deliver different antibiotics, including those used earlier in the treatment pathway. It may also offer relief to patients who struggle with repeated injections, since controlled release can reduce the number of doses needed,” says Motaung.

By the end of his PhD, he hopes to have a fully developed prototype ready for preclinical testing. The new biosafety level two facility at Wits will allow the system to be examined within WADDP and in other specialised labs at the University, accelerating the journey from concept to practical application.

Antimicrobial resistance is advancing faster than the global health system can respond, placing enormous strain on hospitals and turning routine infections into complex medical problems. Research like Motaung’s shows that part of the solution lies in changing how antibiotics are delivered, ensuring that they reach only the bacteria they are meant to treat. In a world running out of effective options, this kind of precision may be essential to safeguarding the future of infection care.

Read the original article on Wits University.