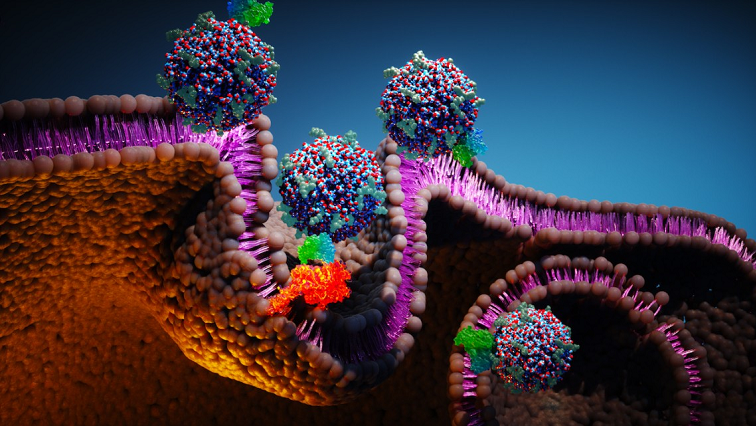

The particles, known as Cornell prime dots, or C’dots, have already been tested in human clinical trials as a cancer diagnostic and a drug delivery system. Now, a study published Dec. 29 in Nature Nanotechnology reports that the nanoparticles themselves can reprogram the tumor microenvironment (TME), transforming immune-resistant tumors into ones that respond far better to treatment.

Dr. Michelle Bradbury, the Endowed Professor of Imaging Research in Radiology and a professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medicine, led the study in collaboration with Ulrich Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Engineering in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. Dr. Jedd Wolchok, the Meyer Director of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, Taha Merghoub, the Meyer Cancer Center’s deputy director, and their laboratory provided critical insights regarding animal models and the tumor microenvironment.

“It’s a very surprising discovery,” said Wiesner, who is also a professor in the Department of Design Tech in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, and whose group originally developed the C’dots. “C’dots on their own – without any pharmaceutical entity on their surface – induce a whole range of antitumoral effects in the TME of melanoma models that, in part, are entirely unexpected.”

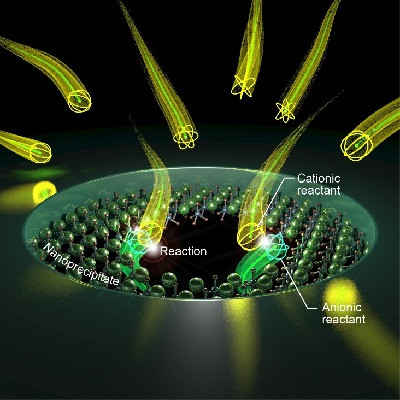

The work builds on a 2016 study in which the team discovered that C’dots trigger ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death, in cancer cells and animal models, reducing tumor growth without conventional chemotherapy. The new study shows that the particles do much more than kill tumor cells directly.

Using aggressive, immunotherapy-resistant melanoma models, the researchers found that C’dots activate multiple antitumor effects simultaneously: They stimulate innate immune responses through pattern-recognition receptors, halt cancer cell proliferation by inducing cell-cycle arrest, reduce immune suppression within the TME, and reprogram key immune cells – including T cells and macrophages – to attack cancer more effectively.

“This platform is not simply acting as a passive carrier or delivery vehicle; these nanoparticles are intrinsically active therapeutic agents,” said Bradbury, who is also a professor of radiology in radiation oncology and of neuroscience in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell, and a neuroradiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Rather than targeting a single pathway, these particles engage multiple mechanisms simultaneously and in ways that conventional therapies cannot easily achieve.”

Aggressive solid TMEs, including those of melanoma, prostate, breast and colon cancers, are considered “cold,” meaning they fail to trigger strong immune responses and often resist immunotherapy. The study shows that C’dots turn these cold tumors “hot,” creating an inflammatory environment that allows immunotherapies to work far more effectively.

In mouse models, a new combinatorial treatment strategy involving administration of C’dots alongside immunotherapies that target both an immune checkpoint and cytokine – a molecule that helps regulate immune responses – led to a significant survival advantage compared with immunotherapy alone. The researchers found the treatments created a synergistic one-two punch: Nanoparticles modulated the immune landscape and improved the performance of immunotherapies, which then delivered a much stronger blow.

“Many aggressive tumors are resistant to immunotherapies alone,” Bradbury said. “What these nanoparticles do is mitigate inhibitory activities within the TME, in turn suppressing tumor growth and limiting resistance.”

The findings suggest that the approach could extend well beyond melanoma. Wiesner noted that the Weill Cornell Medicine team observed similar immune-activating effects of C’dots in other solid tumor models, including prostate and ovarian cancers, and that the findings may point to a deeper biological story.

“From the early stages of evolution, biological organisms have been exposed to nanoparticulate silica on the inside, including through intake of foods like grasses and seaweed,” Wiesner said, citing an earlier study on oral delivery of C’dots. “The hypothesis is that cancer pushes your system out of equilibrium, away from homeostasis. But silica pushes back, and the reason it’s multifactorial is because over millions of years, organisms developed various mechanisms by which silica can basically maintain homeostasis.”

While that idea remains speculative, Wiesner and colleagues are now beginning to explore the hypothesis with Cornell nutritional sciences researchers.

Read the original article on Cornell University.