Rare-earth magnets are essential for electric motors in vehicles, drones, and trains, forming the backbone of modern, environmentally friendly mobility. These are not simple blocks of metal, but carefully engineered materials with a complex internal nanostructure composed of tiny building blocks called phases, each with its own crystal structure, chemistry and physical properties. How magnetization behaves at the interfaces between these tiny building blocks and how well it resists demagnetizing forces ultimately determines the strength and stability of the magnet, and therefore the efficiency and reliability of the motor or generator.

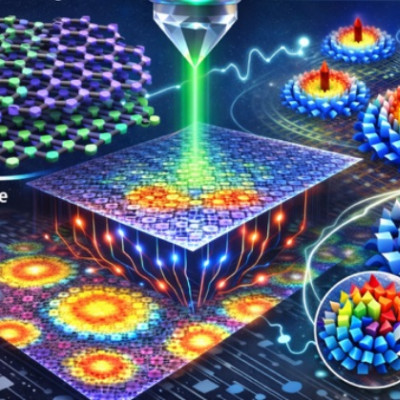

By combining advanced magnetic measurements, various microscopy techniques, and micromagnetic simulations, the researchers investigated a high-performance samarium-cobalt magnet, Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17, which is known for its excellent thermal and chemical stability. Atomic-scale imaging revealed that while high- and medium-performance magnets can appear structurally similar, they differ substantially in their chemical composition at the nanoscale.

Nanostructure is decisive: What happens at interfaces in magnets

A key discovery was that the strongest magnets contain an ultra-thin copper-rich layer- only one to two atoms thick-at the boundary of a critical internal phase. This atomic-scale feature acts as an effective pinning barrier, suppressing demagnetization and enabling reliable operation under extreme conditions.

Another important finding concerns the so-called grain boundary, which separates regions within a crystal that have different orientations but otherwise the same crystal structure. For a long time, grain boundaries were considered the weak link at which demagnetization begins. Now, the researchers of the HoMMage team have discovered that grain boundaries do not significantly impair magnetic performance. Rather, the real potential for improvement lies in the crystalline parts themselves. There, a carefully optimized, atomic-scale nanostructure leads to stronger, more stable magnets. Thus, even tiny changes in how atoms are arranged or how elements are distributed can significantly affect the overall magnet strength and it is the specific structural features at the atomic scale that lead to improved properties of the entire material.

By comparing laboratory observations with micromagnetic computer modeling, the researchers identified the specific microstructural features, known as 'perfect defects', that are responsible for the magnet’s strongest and most stable state. These theoretical insights help to explain why some areas of the magnet perform better than others and will provide valuable guidance for designing even stronger and more efficient magnets in the future without the need for slow and costly trial-and-error testing.

Read the original article on Technical University of Darmstadt.