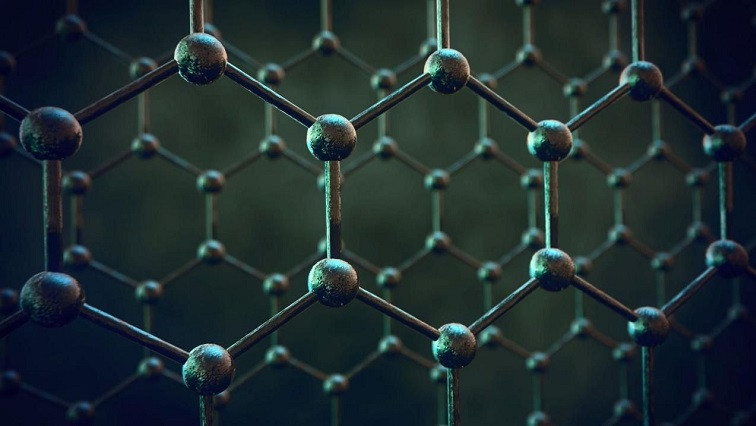

Graphene is a modern wonder material possessing unique properties of strength, flexibility and conductivity whilst being abundant and remarkably cheap to produce, lending it to a multitude of useful applications – especially true when these 2D atom-thick sheets of carbon are split into narrow strips known as Graphene Nanoribbons (GNRs).

New research published in EPJ Plus, authored by Kristiāns Čerņevičs, Michele Pizzochero, and Oleg V. Yazyev, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, aims to better understand the electron transport properties of GNRs and how they are affected by bonding with aromatics. This is a key step in designing technology such chemosensors.

“Graphene nanoribbons – strips of graphene just few nanometres wide – are a new and exciting class of nanostructures that have emerged as potential building blocks for a wide variety of technological applications,” Čerņevičs says.

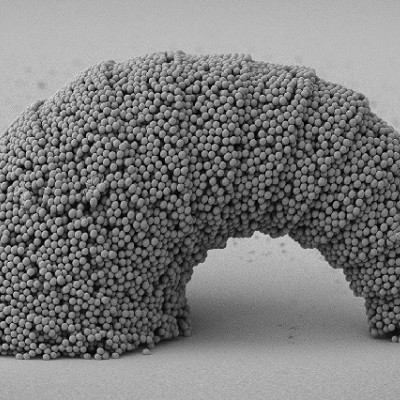

The team performed their investigation with the two forms of GNR , armchair and zigzag, which are categorised by the shape of the edges of the material. These properties are predominantly created by the process used to synthesise them. In addition to this, the EPFL team experimented p-polyphenyl and polyacene groups of increasing length.

“We have employed advanced computer simulations to find out how electrical conductivity of graphene nanoribbons is affected by chemical functionalisation with guest organic molecules that consist of chains composed of an increasing number of aromatic rings,” says Čerņevičs.

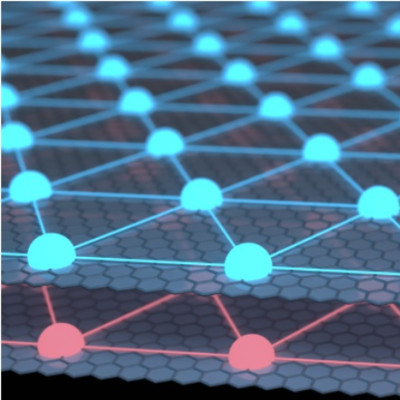

The team discovered that the conductance at energies matching the energy levels of the corresponding isolated molecule was reduced by one quantum, or left unaffected based on whether the number of aromatic rings possessed by the bound molecule was odd or even. The study shows this ‘even–odd effect’ originates from a subtle interplay between the electronic states of the guest molecule spatially localised on the binding sites and those of the host nanoribbon.

“Our findings demonstrate that the interaction of the guest organic molecules with the host graphene nanoribbon can be exploited to detect the ‘fingerprint’ of the guest aromatic molecule, and additionally offer a firm theoretical ground to understand this effect,” Čerņevičs concludes: “Overall, our work promotes the validity of graphene nanoribbons as promising candidates for next-generation chemosensing devices.”

These potentially wearable or implantable sensors will rely heavily on GRBs due to their electrical properties and could spearhead a personalised health revolution by tracking specific biomarkers in patients.

Read the original article on Springer.