Medicinal microrobots could help physicians better treat and prevent diseases. But most of these devices are made with synthetic materials that trigger immune responses in vivo. Now, for the first time, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have used lasers to precisely control neutrophils — a type of white blood cell — as a natural, biocompatible microrobot in living fish. The “neutrobots” performed multiple tasks, showing they could someday deliver drugs to precise locations in the body.

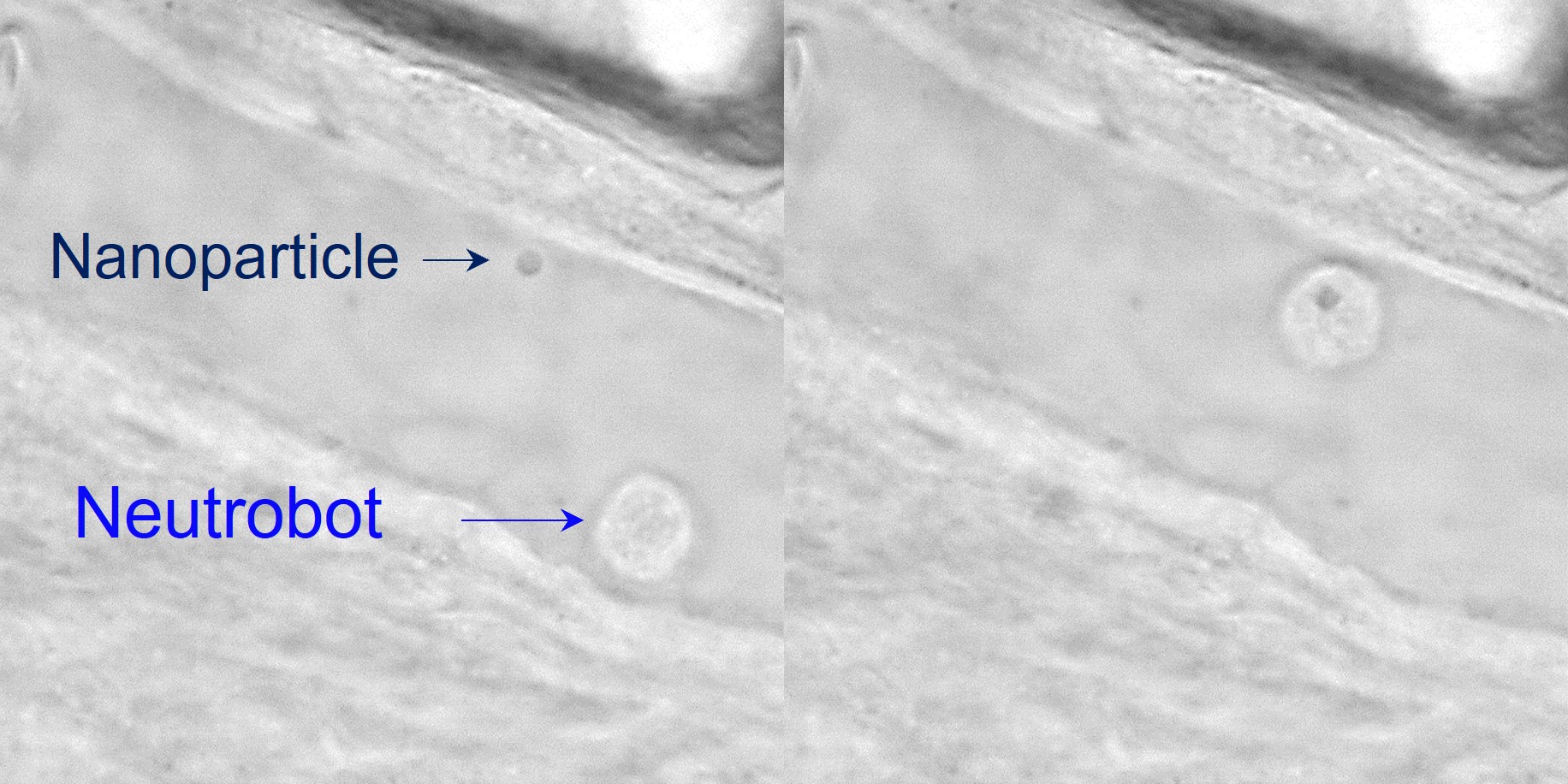

A laser precisely guided a “neutrobot” toward a nanoparticle (left image), which was picked up and transported away

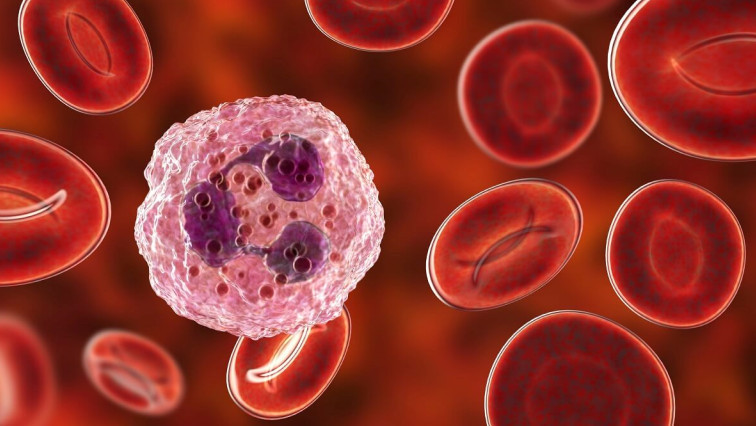

Microrobots currently in development for medical applications would require injections or the consumption of capsules to get them inside an animal or person. But researchers have found that these microscopic objects often trigger immune reactions in small animals, resulting in the removal of microrobots from the body before they can perform their jobs. Using cells already present in the body, such as neutrophils, could be a less invasive alternative for drug delivery that wouldn’t set off the immune system. These white blood cells already naturally pick up nanoparticles and dead red blood cells and can migrate through blood vessels into adjacent tissues, so they are good candidates for becoming microrobots. Previously, researchers have guided neutrophils with lasers in lab dishes, moving them around as “neutrobots.” However, information on whether this approach will work in living animals was lacking. So, Xianchuang Zheng, Baojun Li and colleagues wanted to demonstrate the feasibility of light-driven neutrobots in animals using live zebrafish.

The researchers manipulated and maneuvered neutrophils in zebrafish tails, using focused laser beams as remote optical tweezers. The light-driven microrobot could be moved up to a velocity of 1.3 µm/s, which is three times faster than a neutrophil naturally moves. In their experiments, the researchers used the optical tweezers to precisely and actively control the functions that neutrophils conduct as part of the immune system. For instance, a neutrobot was moved through a blood vessel wall into the surrounding tissue. Another one picked up and transported a plastic nanoparticle, showing its potential for carrying medicine. And when a neutrobot was pushed toward red blood cell debris, it engulfed the pieces. Surprisingly, at the same time, a different neutrophil, which wasn’t controlled by a laser, tried to naturally remove the cellular debris. Because they successfully controlled neutrobots in vivo, the researchers say this study advances the possibilities for targeted drug delivery and precise treatment of diseases.

Read the original article on American Chemical Society (ACS).