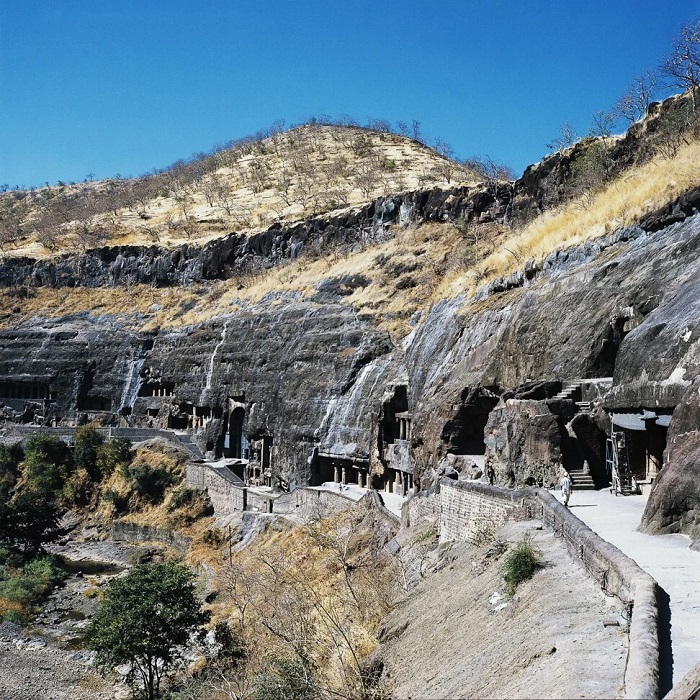

Featuring elephants, elaborate headdresses, finely wrought jewellery, flowers, jars of wine (or perhaps water), buxom women playing musical instruments, helmeted foreigners and religious symbols, the ancient Buddhist art of the Ajanta Caves in western India is considered a supremely beautiful historical record dating from as early as two millennia ago.

Now, an image of a detail from one of the murals has been deposited in an underground archive, in a decommissioned coal mine deep in an Arctic mountain on an island off the northern coast of Norway.

Originally photographed by Indian art historian Benoy Behl in the early 1990s using lowlight photography techniques he developed for the work, the image is of King Mahajanaka seen renouncing worldly pleasures in one of the elaborate Ajanta murals. Potentially the first of many of Behl's Ajanta photos destined for the archive, the image is safe from cyberattacks, terrorism and natural disasters, and experts say it will be preserved for generations to come.

Get the latest insights and analysis from our Global Impact newsletter on the big stories originating in China.

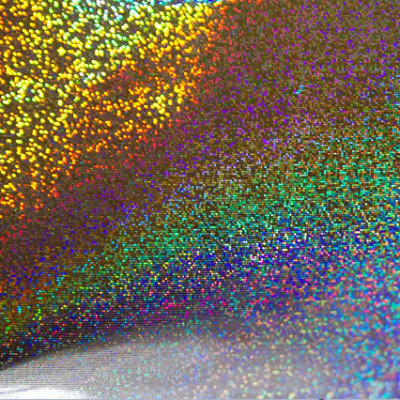

Behl's photograph was digitised using high-end, pixel-level scanning, then converted to ultra-high-resolution film using the latest nanotechnology. Patricia Alfheim, from Norwegian digital data storage company Piql, says a 35mm silver halide photosensitive film that has been longevity-tested to survive for more than 500 years was used to store the image.

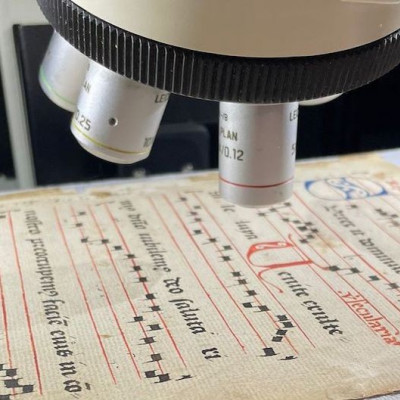

The original detail shot of the Ajanta painting of King Mahajanaka.

"The cool, dark and dry conditions inside the mountain increase this lifetime even further," she adds. "PiqlFilm has been designed to be self-contained, meaning that all the information you need to recover the data is stored on the medium in human-readable text."

With the support of the Indian government, the film of the king's image was put in a purpose-built box and then into a protective barrier bag for deposit in the steel vault in the Arctic World Archive - a commercial enterprise owned by Piql - on the Svalbard archipelago.

Behl's specific lowlight photographic techniques developed to photograph the Ajanta murals and other artworks were necessary to preserve the art, because the ancient caves have never been well-lit; ordinarily, flash photography is prohibited, although special permission could be sought. Even so, earlier attempts to take photos of the images had largely failed, Behl says.

"There was unwanted surface reflection from the painted veneers due to conventional flash," he explains.

The technique he developed allowed him to capture images even when the light was so low he could barely see his hand in front of his face.

The Ajanta Caves complex in India’s Maharashtra state.

The Ajanta Caves complex in India’s Maharashtra state.

Behl says he used long exposures and measured the "colour temperature" of the available light. The thousands of photographs he took were a success, and finally allowed the world to see the extraordinary centuries-old images that had been hidden in the caves.

The murals and carvings in the dark recesses and colonnaded galleries of Ajanta tell the stories of the lives of Gautama Buddha through 550 narratives from Jataka, Buddhist literature describing the Buddha's lives. The murals are crowded with people and alive with drama, providing endless material for historical speculation.

"The centuries have taken their toll on the paintings, and their magnificence has been obscured by gawking visitors and conditions inside the caves," Behl says, adding that he has digitally altered and "restored" the art in his photos, in much the way that art restoration experts can retouch or fill in holes or scratches in artworks. The image deposited in the Arctic archive has not been edited.

"Over a period of many years, I have digitally restored much of the damaged masterpiece paintings," Behl adds. "They can now be seen in their true glory."

He says digital software is necessary to make such meticulous restoration possible. "However, this has been a painstaking exercise, incorporating a deep art-historical understanding of the paintings, their grace and aesthetics. Anything done mechanically and merely with technical skills without an understanding of art and aesthetics would ruin the art."

The gracious and elegant Ajanta art speaks of a golden age of Indian painting. It has intrigued researchers, scholars and artists from around the world ever since a cave was first discovered by Westerners more than 200 years ago, when an English cavalry officer on a tiger hunt following a young Indian guide scanned the steep cliff face and found the caves.

Brandishing a clump of burning grass to provide some light, the soldier and his military companions explored the cave, finding skeletons and an abundance of religious art. The soldier left his name, John Smith, and the date, April 28, 1819, carved into one of the cave's statues of the Bodhisattva, a figure representing one of the lives of the Buddha before he achieved Nirvana.

PiqlFilm, a 35mm, ultra-high-resolution nanofilm optimised and designed for the preservation of digital data.

Smith and his companions had found a long hall cut straight into the rock of the cliff, lined on either side with 39 octagonal pillars. The dome of a Buddhist stupa rose at one end of the hall.

Another 30 Ajanta caves were later found, lofty chaityagriha (prayer halls) and vihara (monasteries) cut into the walls of the horseshoe-shaped ravine in the serene Waghora River valley, 100km (62 miles) north of the town of Aurangabad in Maharashtra state, and about 430km east of Mumbai. Regarded as supremely important historically and artistically, the Ajanta and nearby Ellora caves were declared Unesco World Heritage sites in 1983.

Almost from the start, experts working on the art of the Ajanta caves understood there were two different stages of work to be explored. The cave Smith and his companions found, already known to the local Bhil people, was later named Cave 10. It was at the centre of the cliff and, along with five others nearby, could be dated to the first or second century BC. But most of the other Ajanta caves cut into the cliff, and nearly all the stupendously rich murals, telling stories of how lives were lived many centuries ago, are now thought to date from nearly 600 years later.

Time, smoke, graffiti and unfortunate attempts at restoration damaged some of the paintings almost irreparably. Early random visitors peeled off parts of murals, and carved their names into the walls.

For much of the 20th century, the art in Caves 9 and 10 was hidden from view, obscured by deteriorating shellac, an attempt at protection that rapidly obscured the images.

Eventually, painstaking work beginning in the late 1990s using infrared light, and the latest in conservation technology, managed to remove most of the dirt and layers of soot and shellac from about 10 square metres of the murals.

The work revealed the oldest known Indian paintings (aside from stick-figure pictograms left by hunters in the wild) and the oldest Buddhist paintings in existence, dating from 300 years after the death of the Buddha.

Inside Cave 4 of the Ajanta Caves complex.

Foreigners with distinctive physical features, skin colour and costumes can be seen in the art. These murals suggest the region of many centuries ago was a prosperous trading nation on friendly terms with neighbouring states. Blue lapis lazuli pigment used in the murals was almost certainly imported from Afghanistan or Iran, experts say, and the clothing adorning the foreign figures looks to be from Central Asia, Persia and possibly east Africa.

Behl remains amazed at the wealth and intricacy of the Ajanta murals, and the beauty of the pillars and statues. "The late poet and director of the British Museum, Laurence Binyon, believed that 'every study of Asian art would ultimately end at Ajanta'," he says.

Behl wrote a paper on the Ajanta cave art, which was submitted to the Arctic archive along with his photograph. In it, he says: "The ancient murals of India display a quality of art which is sublime and unexpected in paintings of that age."

Read the original article on South China Morning Post.