"What we're hoping is that we'll be able to get fingerprints that current powders can't get."

Nick Ross is a PhD student at the University of Leicester's School of Chemistry, which is studying this flourescent nanomaterial in collaboration with other researchers from the UK and Brazil.

The fingerprints we leave behind are made of mostly water, in the form of sweat and natural oils. And they can evaporate in certain conditions, leaving little evidence behind.

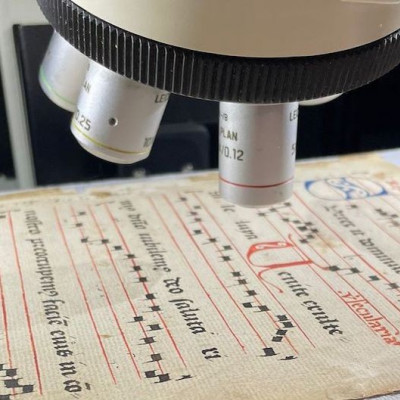

Ross says dusting for prints using nanoparticles, which are much finer than most powders, means more detail can be captured.

And - less of the fingerprint residue is needed for the particles to stick to.

"We should be able to get fingerprints that maybe someone's washed their hands more recently and they've touched something, but they've left less residue behind. But we're going to be able to get that using a more sensitive powder."

It also means a print's owner could potentially be identified even years later.

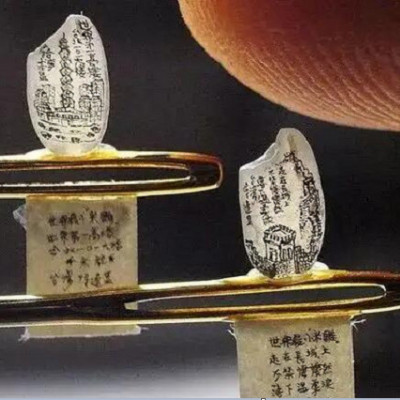

The new material consists of a silica nanoparticle, a fluorescent dye and chitosan, which can obtained from powdered shrimp, crab or lobster shells.

Robert Hillman, Professor of Physical Chemistry at the university, is hopeful that it could mean breakthroughs in crime scene investigations.

“There is, of course, the interesting question of how ancient, if you like, evidence we could examine this way. So could we go back and visit cold cases? I would be reasonably optimistic about this because there will inevitably be some residue left. Perhaps not very much, but we don't need very much. It will depend on the type of surface."

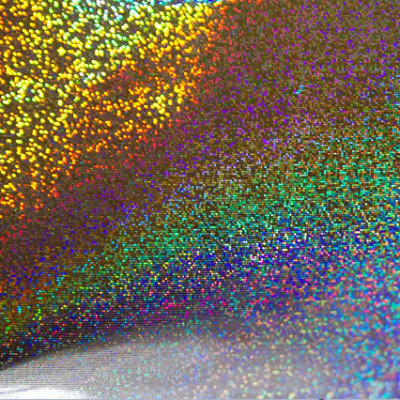

Tests on the nanomaterial have found it sticks to residues on a range of different surfaces... including cash.

That's good news for investigators looking to follow the money.

“Banknotes can be particularly difficult to get fingerprints off of for a number of reasons. They've got lots of patterns all over them // the thickness and the shape of the patterns can look really similar to fingerprint detail. This image is particularly nice because the fingerprint is so different to the banknote itself. It's so clear, the fluorescence of the particles are so strong that there's no chance you mistake the detail for the banknote.”

The research has been published by the Royal Society of Chemistry.

More than a century after the widespread acceptance of fingerprints in courts around the world, it could be about to shed some light on crucial evidence that has until now remained invisible.

Read the original article on Yahoo News.