| Date | 14th, Aug 2018 |

|---|

Made up of over 90 percent air by weight, aerogels are the lightest materials in existence and among the best thermal insulators. But their cloudy appearance means they don't lend themselves well to windows, which are one of the worst offenders for letting heat escape a building. Now, researchers at Colorado University Boulder have found a way to make them transparent, recycling a beer by-product in the process.

Trapped air is key to thermal insulators. Clothes keep you warm by trapping air close to your skin where your body heat warms it up, and materials like wool and goose down feel warmer because their higher surface area can hold more air. Since aerogels are mostly air, that makes them terrific insulators, and they've been put to work in bricks, tiny houses and winter jackets.

But the very structure that makes them great insulators makes them terrible windows. Aerogels have a crisscrossing structure of solid material that creates billions of pores to hold air, but that also scatters a lot of light, giving them a cloudy look sometimes called "frozen smoke."

So the CU Boulder team set out to develop a more transparent aerogel that could be fitted over windows, letting light pass through while keeping heat in. To do so, the researchers turned to cellulose, a common plant sugar that can be manipulated so its molecules link up in a uniform lattice pattern.

CU Boulder

But it's where the team sourced this cellulose that's particularly clever – liquid waste from the beer-brewing process. The horribly unappetizing by-product known as beer wort is normally just discarded, but the researchers found they could use it to produce cellulose for their aerogel.

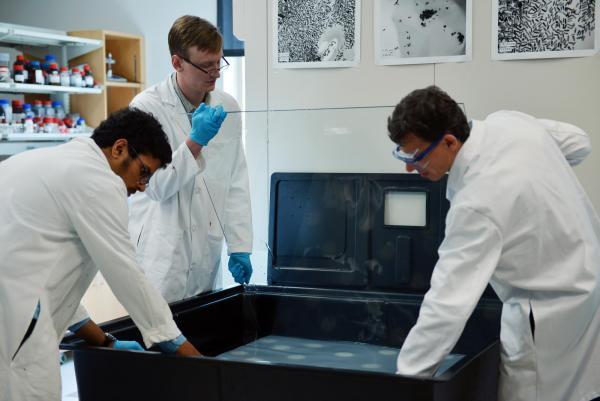

First, they collected tubs of the stuff from local breweries. Then, they added specialized bacteria that can create cellulose from beer wort over about two weeks. With the material in hand, the team can then induce the cellulose to self-assemble into nanofibers to make the gel. The end result is a thin film that's transparent and highly heat-resistant.

The team says that the transparent aerogel could be most useful as a film that sticks over existing windows to greatly improve their thermal insulation, in turn making heating more efficient and less expensive.

"Windows are incredibly expensive to replace," says Andrew Hess, co-author of the study. "We're envisioning a retrofitting product that would basically be a peel-and-stick film that a consumer would buy at Home Depot. We also see our technology being enabling for so many other applications, including smart clothes, for insulating cars and protecting firefighters."

CU Boulder

But these applications might not be limited to Earth either – a few months ago the team won NASA's 2018 iTech competition, pitching the aerogel as an insulator for otherworldly windows.

"Transparency is an enabling feature because you can use this gel in windows, and you could use it in extraterrestrial habitats," says Ivan Smalyukh, corresponding author of the study. "You could harvest sunlight through that thermally insulating material and store the energy inside, protecting yourself from those big oscillations in temperature that you have on Mars or on the moon."

The research was published in the journal Nano Energy. The team demonstrates the fabrication process in the video below.

Source: CU Boulder

From beer to windows