| Date | 6th, Nov 2018 |

|---|

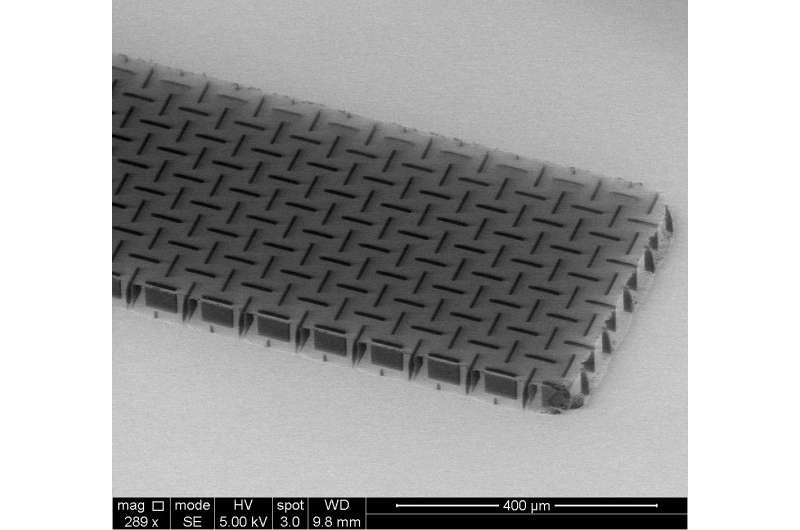

Nanocardboard is made out of an aluminum oxide film with a thickness of tens of nanometers, forming a hollow plate with a height of tens of microns. Its sandwich structure, similar to that of corrugated cardboard, makes it more than ten thousand times as stiff as a solid plate of the same mass. A square centimeter of nanocardboard weighs less than a thousandth of a gram and can spring back into shape after being bent in half. Credit: University of Pennsylvania

Nanocardboard is made out of an aluminum oxide film with a thickness of tens of nanometers, forming a hollow plate with a height of tens of microns. Its sandwich structure, similar to that of corrugated cardboard, makes it more than ten thousand times as stiff as a solid plate of the same mass. A square centimeter of nanocardboard weighs less than a thousandth of a gram and can spring back into shape after being bent in half. Credit: University of Pennsylvania

When choosing materials to make something, trade-offs need to be made between a host of properties, such as thickness, stiffness and weight. Depending on the application in question, finding just the right balance is the difference between success and failure

Now, a team of Penn Engineers has demonstrated a new material they call "nanocardboard," an ultrathin equivalent of corrugated paper cardboard. A square centimeter of nanocardboard weighs less than a thousandth of a gram and can spring back into shape after being bent in half.

Nanocardboard is made out of an aluminum oxide film with a thickness of tens of nanometers, forming a hollow plate with a height of tens of microns. Its sandwich structure, similar to that of corrugated cardboard, makes it more than ten thousand times as stiff as a solid plate of the same mass.

Nanocardboard's stiffness-to-weight ratio makes it ideal for aerospace and microrobotic applications, where every gram counts. In addition to unprecedented mechanical properties, nanocardboard is a supreme thermal insulator, as it mostly consists of empty space.

Future work will explore an intriguing phenomenon that results from a combination of properties: shining a light on a piece of nanocardboard allows it to levitate. Heat from the light creates a difference in temperatures between the two sides of the plate, which pushes a current of air molecules out through the bottom.

Igor Bargatin, Class of 1965 Term Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics, along with lab members Chen Lin and Samuel Nicaise, led the study. They collaborated with Prashant Purohit, professor in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics, and his graduate student Jaspreet Singh, as well as Gerald Lopez and Meredith Metzler of the Singh Center for Nanotechnology. Bargatin lab members Drew Lilley, Joan Cortes, Pengcheng Jiao, and Mohsen Azadi also contributed to the study.

They published their results in the journal Nature Communications.