Dec 18, 2018

(Nanowerk News) The seeds of some plants such as basil, watercress or plantain form a mucous envelope as soon as they come into contact with water. This cover consists of cellulose in particular, which is an important structural component of the primary cell wall of green plants, and swelling pectins, plant polysaccharides.

In order to be able to investigate its physical properties, a research team from the Zoological Institute at Kiel University (CAU) used a special drying method, which gently removes the water from the cellulosic mucous sheath. The team discovered that this method can produce extremely strong nanofibres from natural cellulose. In future, they could be especially interesting for applications in biomedicine.

The team’s results recently appeared as the cover story in the journal Applied Materials & Interfaces ("Friction-Active Surfaces Based on Free-Standing Anchored Cellulose Nanofibrils").

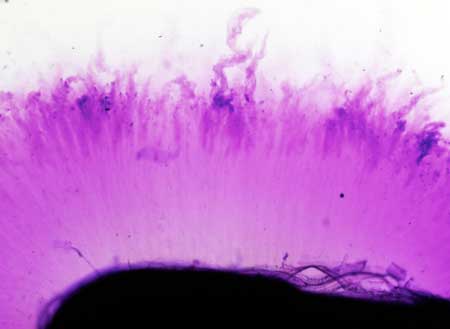

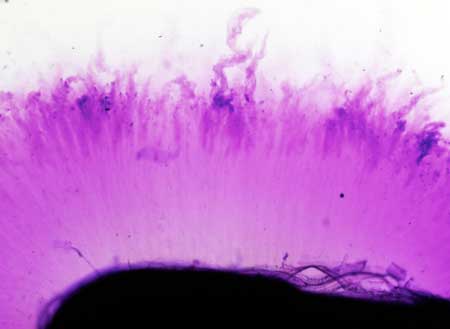

A detailed view under the microscope shows cellulose fibres on the surface of a seed of Artemisia leucodes from the family of composite plants. The actually colourless fibres were coloured purple for better visibility. (Image: Kreitschitz)

Thanks to their slippery mucous sheath, seeds can slide through the digestive tract of birds undigested. They are excreted unharmed, and can be dispersed in this way. It is presumed that the mucous layer provides protection. "In order to find out more about the function of the mucilage, we first wanted to study the structure and the physical properties of this seed envelope material," said Zoology Professor Stanislav N. Gorb, head of the "Functional Morphology and Biomechanics" working group at the CAU. In doing so they discovered that its properties depend on the alignment of the fibres that anchor them to the seed surface.

A detailed view under the microscope shows cellulose fibres on the surface of a seed of Artemisia leucodes from the family of composite plants. The actually colourless fibres were coloured purple for better visibility. (Image: Kreitschitz)

Thanks to their slippery mucous sheath, seeds can slide through the digestive tract of birds undigested. They are excreted unharmed, and can be dispersed in this way. It is presumed that the mucous layer provides protection. "In order to find out more about the function of the mucilage, we first wanted to study the structure and the physical properties of this seed envelope material," said Zoology Professor Stanislav N. Gorb, head of the "Functional Morphology and Biomechanics" working group at the CAU. In doing so they discovered that its properties depend on the alignment of the fibres that anchor them to the seed surface.

A detailed view under the microscope shows cellulose fibres on the surface of a seed of Artemisia leucodes from the family of composite plants. The actually colourless fibres were coloured purple for better visibility. (Image: Kreitschitz)

Thanks to their slippery mucous sheath, seeds can slide through the digestive tract of birds undigested. They are excreted unharmed, and can be dispersed in this way. It is presumed that the mucous layer provides protection. "In order to find out more about the function of the mucilage, we first wanted to study the structure and the physical properties of this seed envelope material," said Zoology Professor Stanislav N. Gorb, head of the "Functional Morphology and Biomechanics" working group at the CAU. In doing so they discovered that its properties depend on the alignment of the fibres that anchor them to the seed surface.

A detailed view under the microscope shows cellulose fibres on the surface of a seed of Artemisia leucodes from the family of composite plants. The actually colourless fibres were coloured purple for better visibility. (Image: Kreitschitz)

Thanks to their slippery mucous sheath, seeds can slide through the digestive tract of birds undigested. They are excreted unharmed, and can be dispersed in this way. It is presumed that the mucous layer provides protection. "In order to find out more about the function of the mucilage, we first wanted to study the structure and the physical properties of this seed envelope material," said Zoology Professor Stanislav N. Gorb, head of the "Functional Morphology and Biomechanics" working group at the CAU. In doing so they discovered that its properties depend on the alignment of the fibres that anchor them to the seed surface.