Feb 26, 2019

(Nanowerk News) In recent years, electronic data processing has been evolving in one direction only: The industry has downsized its components to the nanometer range. But this process is now reaching its physical limits.

Researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) are therefore exploring spin waves or so-called magnons – a promising alternative for transporting information in more compact microchips. Cooperating with international partners, they have successfully generated and controlled extremely short-wavelength spin waves.

The physicists achieved this feat by harnessing a natural magnetic phenomenon, as they explain in the journal Nature Nanotechnology ("Emission and propagation of 1D and 2D spin-waves with nanoscale wavelengths in anisotropic spin textures")

.

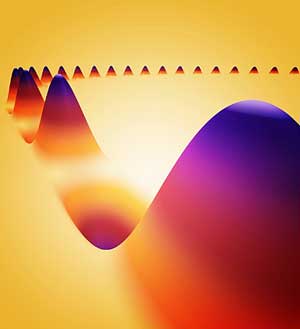

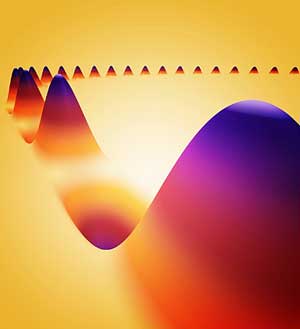

A spin wave spreading along a magnetic domain wall. (Image: HZDR/Juniks)

For a long time, there has been one reliable rule of thumb in the world of information technology: The number of transistors on a microprocessor doubles approximately every two years. The resulting performance boost brought us the digital opportunities we now take for granted, from high speed internet to the smartphone.

But as the conductors on the chip get ever more minute, we are starting to face problems, as Dr. Sebastian Wintz from HZDR’s Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research explains: “The electrons that flow through our modern microprocessors heat up the chip due to electrical resistance. Beyond a certain point, the chips simply fail because the heat can no longer escape.” This also prevents a further increase in the speed of the components.

This is why the physicist, who is also currently working at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland, envisions a different future for information carriers. Instead of electrical currents, Wintz and his colleagues are capitalizing on a specific property of electrons called ‘spin’. The tiny particles behave as if they were constantly rotating around their own axis, thus creating a magnetic moment.

In certain magnetic materials, like iron or nickel, the spins are typically parallel to each other. If the orientation of these spins is changed in one place, that disruption travels to the neighboring particles, triggering a spin wave which can be used to encode and distribute information. “In this scenario, the electrons remain where they are,” says Wintz, describing their advantage. “They hardly generate any heat, which means that spin-based components might require far less energy.”

A spin wave spreading along a magnetic domain wall. (Image: HZDR/Juniks)

For a long time, there has been one reliable rule of thumb in the world of information technology: The number of transistors on a microprocessor doubles approximately every two years. The resulting performance boost brought us the digital opportunities we now take for granted, from high speed internet to the smartphone.

But as the conductors on the chip get ever more minute, we are starting to face problems, as Dr. Sebastian Wintz from HZDR’s Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research explains: “The electrons that flow through our modern microprocessors heat up the chip due to electrical resistance. Beyond a certain point, the chips simply fail because the heat can no longer escape.” This also prevents a further increase in the speed of the components.

This is why the physicist, who is also currently working at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland, envisions a different future for information carriers. Instead of electrical currents, Wintz and his colleagues are capitalizing on a specific property of electrons called ‘spin’. The tiny particles behave as if they were constantly rotating around their own axis, thus creating a magnetic moment.

In certain magnetic materials, like iron or nickel, the spins are typically parallel to each other. If the orientation of these spins is changed in one place, that disruption travels to the neighboring particles, triggering a spin wave which can be used to encode and distribute information. “In this scenario, the electrons remain where they are,” says Wintz, describing their advantage. “They hardly generate any heat, which means that spin-based components might require far less energy.”

A spin wave spreading along a magnetic domain wall. (Image: HZDR/Juniks)

For a long time, there has been one reliable rule of thumb in the world of information technology: The number of transistors on a microprocessor doubles approximately every two years. The resulting performance boost brought us the digital opportunities we now take for granted, from high speed internet to the smartphone.

But as the conductors on the chip get ever more minute, we are starting to face problems, as Dr. Sebastian Wintz from HZDR’s Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research explains: “The electrons that flow through our modern microprocessors heat up the chip due to electrical resistance. Beyond a certain point, the chips simply fail because the heat can no longer escape.” This also prevents a further increase in the speed of the components.

This is why the physicist, who is also currently working at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland, envisions a different future for information carriers. Instead of electrical currents, Wintz and his colleagues are capitalizing on a specific property of electrons called ‘spin’. The tiny particles behave as if they were constantly rotating around their own axis, thus creating a magnetic moment.

In certain magnetic materials, like iron or nickel, the spins are typically parallel to each other. If the orientation of these spins is changed in one place, that disruption travels to the neighboring particles, triggering a spin wave which can be used to encode and distribute information. “In this scenario, the electrons remain where they are,” says Wintz, describing their advantage. “They hardly generate any heat, which means that spin-based components might require far less energy.”

A spin wave spreading along a magnetic domain wall. (Image: HZDR/Juniks)

For a long time, there has been one reliable rule of thumb in the world of information technology: The number of transistors on a microprocessor doubles approximately every two years. The resulting performance boost brought us the digital opportunities we now take for granted, from high speed internet to the smartphone.

But as the conductors on the chip get ever more minute, we are starting to face problems, as Dr. Sebastian Wintz from HZDR’s Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research explains: “The electrons that flow through our modern microprocessors heat up the chip due to electrical resistance. Beyond a certain point, the chips simply fail because the heat can no longer escape.” This also prevents a further increase in the speed of the components.

This is why the physicist, who is also currently working at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland, envisions a different future for information carriers. Instead of electrical currents, Wintz and his colleagues are capitalizing on a specific property of electrons called ‘spin’. The tiny particles behave as if they were constantly rotating around their own axis, thus creating a magnetic moment.

In certain magnetic materials, like iron or nickel, the spins are typically parallel to each other. If the orientation of these spins is changed in one place, that disruption travels to the neighboring particles, triggering a spin wave which can be used to encode and distribute information. “In this scenario, the electrons remain where they are,” says Wintz, describing their advantage. “They hardly generate any heat, which means that spin-based components might require far less energy.”