Mar 07, 2019

(Nanowerk News) To protect graphene from performance-impairing wrinkles and contaminants that mar its surface during device fabrication, MIT researchers have turned to an everyday material: wax.

Graphene is an atom-thin material that holds promise for making next-generation electronics. Researchers are exploring possibilities for using the exotic material in circuits for flexible electronics and quantum computers, and in a variety of other devices.

But removing the fragile material from the substrate it’s grown on and transferring it to a new substrate is particularly challenging. Traditional methods encase the graphene in a polymer that protects against breakage but also introduces defects and particles onto graphene’s surface. These interrupt electrical flow and stifle performance.

In a paper published in Nature Communications ("Paraffin-enabled graphene transfer"), the researchers describe a fabrication technique that applies a wax coating to a graphene sheet and heats it up. Heat causes the wax to expand, which smooths out the graphene to reduce wrinkles. Moreover, the coating can be washed away without leaving behind much residue.

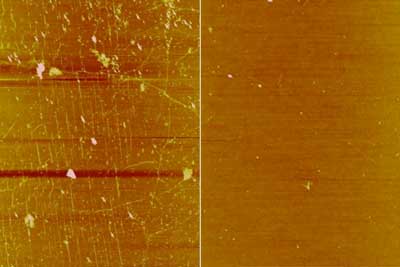

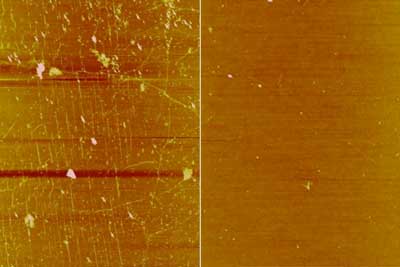

The image on the right shows a graphene sheet coated with wax during the substrate-transfer step. This method drastically reduced wrinkles on the graphene’s surface compared to a traditional polymer coating (left). (Courtesy of the researcher3)

In experiments, the researchers’ wax-coated graphene performed four times better than graphene made with a traditional polymer-protecting layer. Performance, in this case, is measured in “electron mobility” — meaning how fast electrons move across a material’s surface — which is hindered by surface defects.

“Like waxing a floor, you can do the same type of coating on top of large-area graphene and use it as layer to pick up the graphene from a metal growth substrate and transfer it to any desired substrate,” says first author Wei Sun Leong, a postdoc in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). “This technology is very useful, because it solves two problems simultaneously: the wrinkles and polymer residues.”

Co-first author Haozhe Wang, a PhD student in EECS, says using wax may sound like a natural solution, but it involved some thinking outside the box — or, more specifically, outside the laboratory: “As students, we restrict ourselves to sophisticated materials available in lab. Instead, in this work, we chose a material that commonly used in our daily life.”

Joining Leong and Wang on the paper are: Jing Kong and Tomas Palacios, both EECS professors; Markus Buehler, professor and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE); and six other graduate students, postdocs, and researchers from EECS, CEE, and the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

The image on the right shows a graphene sheet coated with wax during the substrate-transfer step. This method drastically reduced wrinkles on the graphene’s surface compared to a traditional polymer coating (left). (Courtesy of the researcher3)

In experiments, the researchers’ wax-coated graphene performed four times better than graphene made with a traditional polymer-protecting layer. Performance, in this case, is measured in “electron mobility” — meaning how fast electrons move across a material’s surface — which is hindered by surface defects.

“Like waxing a floor, you can do the same type of coating on top of large-area graphene and use it as layer to pick up the graphene from a metal growth substrate and transfer it to any desired substrate,” says first author Wei Sun Leong, a postdoc in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). “This technology is very useful, because it solves two problems simultaneously: the wrinkles and polymer residues.”

Co-first author Haozhe Wang, a PhD student in EECS, says using wax may sound like a natural solution, but it involved some thinking outside the box — or, more specifically, outside the laboratory: “As students, we restrict ourselves to sophisticated materials available in lab. Instead, in this work, we chose a material that commonly used in our daily life.”

Joining Leong and Wang on the paper are: Jing Kong and Tomas Palacios, both EECS professors; Markus Buehler, professor and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE); and six other graduate students, postdocs, and researchers from EECS, CEE, and the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

The image on the right shows a graphene sheet coated with wax during the substrate-transfer step. This method drastically reduced wrinkles on the graphene’s surface compared to a traditional polymer coating (left). (Courtesy of the researcher3)

In experiments, the researchers’ wax-coated graphene performed four times better than graphene made with a traditional polymer-protecting layer. Performance, in this case, is measured in “electron mobility” — meaning how fast electrons move across a material’s surface — which is hindered by surface defects.

“Like waxing a floor, you can do the same type of coating on top of large-area graphene and use it as layer to pick up the graphene from a metal growth substrate and transfer it to any desired substrate,” says first author Wei Sun Leong, a postdoc in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). “This technology is very useful, because it solves two problems simultaneously: the wrinkles and polymer residues.”

Co-first author Haozhe Wang, a PhD student in EECS, says using wax may sound like a natural solution, but it involved some thinking outside the box — or, more specifically, outside the laboratory: “As students, we restrict ourselves to sophisticated materials available in lab. Instead, in this work, we chose a material that commonly used in our daily life.”

Joining Leong and Wang on the paper are: Jing Kong and Tomas Palacios, both EECS professors; Markus Buehler, professor and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE); and six other graduate students, postdocs, and researchers from EECS, CEE, and the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

The image on the right shows a graphene sheet coated with wax during the substrate-transfer step. This method drastically reduced wrinkles on the graphene’s surface compared to a traditional polymer coating (left). (Courtesy of the researcher3)

In experiments, the researchers’ wax-coated graphene performed four times better than graphene made with a traditional polymer-protecting layer. Performance, in this case, is measured in “electron mobility” — meaning how fast electrons move across a material’s surface — which is hindered by surface defects.

“Like waxing a floor, you can do the same type of coating on top of large-area graphene and use it as layer to pick up the graphene from a metal growth substrate and transfer it to any desired substrate,” says first author Wei Sun Leong, a postdoc in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). “This technology is very useful, because it solves two problems simultaneously: the wrinkles and polymer residues.”

Co-first author Haozhe Wang, a PhD student in EECS, says using wax may sound like a natural solution, but it involved some thinking outside the box — or, more specifically, outside the laboratory: “As students, we restrict ourselves to sophisticated materials available in lab. Instead, in this work, we chose a material that commonly used in our daily life.”

Joining Leong and Wang on the paper are: Jing Kong and Tomas Palacios, both EECS professors; Markus Buehler, professor and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE); and six other graduate students, postdocs, and researchers from EECS, CEE, and the Department of Mechanical Engineering.