A recent study, published in Nature Communications, aims to answer a basic question — how do nanoparticles melt? While this question has been of significant interest among scientists for the past 100 years, it still has not been answered. Early theoretical models describing melting date back to about a century ago, and even the most applicable models are about 50 years old.

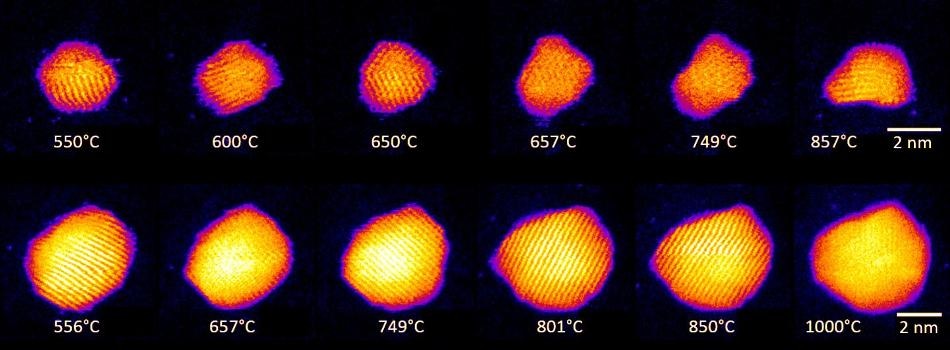

Shape changes in Au nanoclusters, indicating cluster surface melting at high temperatures. Images of two individual clusters containing 561 and 2530 atoms are shown. (Image credit: Swansea University)

Shape changes in Au nanoclusters, indicating cluster surface melting at high temperatures. Images of two individual clusters containing 561 and 2530 atoms are shown. (Image credit: Swansea University)

Professor Richard Palmer, who led the team based at the Swansea University's College of Engineering said of the study: "Although melting behaviour was known to change on the nanoscale, the way in which nanoparticles melt was an open question. Given that the theoretical models are now rather old, there was a clear case for us to carry out our new imaging experiments to see if we could test and improve these theoretical models."

In their experiments, the researchers used gold as it behaves as a model system for noble and other metals. The team reached at their results by imaging gold nanoparticles, with diameters measuring from 2 nm to 5 nm, via aberration corrected scanning transmission electron microscope. Their observations were subsequently reinforced by mass quantum mechanical simulations.

We were able to prove the dependence of the melting point of the nanoparticles on their size and for the first time see directly the formation of a liquid shell around a solid core in the nanoparticles over a wide region of elevated temperatures, in fact for hundreds of degrees. This helps us to describe accurately how nanoparticles melt and to predict their behaviour at elevated temperatures. This is a science breakthrough in a field we can all relate to — melting — and will also help those producing nanotech devices for a range of practical and everyday uses, including medicine, catalysis, and electronics.

Richard Palmer, Professor, College of Engineering, Swansea University